Kasurian in Season: A Letter from the Editors #3

Concluding Kasurian’s Autumn 2025 issue.

With Democracy Will Not Survive the Age of Consumption, Kasurian’s Autumn 2025 issue has concluded.

This issue began with The Closing of the Muslim Mind, which traced the institutional annihilation of Islamic civilisation between 1917 and 1947 through three events: the Ottoman dissolution, the rise of Communism in Russia, and the Partition of India. These catastrophes were devastating, but any one of them might have been survivable on its own. Civilisations have recovered from territorial loss, foreign occupation, and demographic upheaval. Islamic civilisation itself had survived the Mongol invasions, integrating the conquerors and eventually reaching new heights under the gunpowder empires. Even in the 19th century, despite encroaching colonialism and military defeats on all fronts, a genuine intellectual renaissance had emerged with a flowering of print culture, transnational networks, and public debate that suggested the capacity for renewal remained intact. These movements have been discounted simply because they failed. Yet the structural factors that saw the wholesale evisceration of Islamic civilisation in the 20th century should not discount their genuine efforts, successes, or even the lessons of their failures.

The three catastrophes did not occur in isolation. They compounded each other. Each destroyed a different pillar of civilisational infrastructure, and together they ensured that no safe harbour remained where the work of transition into industrial modernity, haltingly begun in the short 19th century, could continue. The Ottoman collapse eliminated the central political authority and patronage networks that had sustained intellectual life across the Arab and Turkish-speaking worlds. Communist repression isolated Central Asia and the Caucasus, destroying and displacing various communities such as the Tatars, Kazakhs, and Circassians, and decapitating the Jadid reform movement that might have offered a model for synthesis. Partition fractured the Indian subcontinent, severing the Indo-Islamic world into two wounded states incapable of continuing the once subcontinent-spanning traditions that had made the region a beacon of Islamic culture and learning. What was lost was not merely ideas but the material basis for producing ideas: the governing elites, the merchant bourgeoisie, the transnational scholarly networks, the systems of patronage and endowment that had sustained knowledge production for centuries.

This material dimension is precisely what is missing from most discussions of why the Muslim world has stagnated over the past century while East Asia, Europe, and North America pulled ahead. We speak of colonialism, of Western imperialism, of the corruption of leaders or the backwardness of the masses – abstractions that fail to account for the totality of the rupture. Knowledge and civilisation are not born solely from philosophical inquiry; they require class structures capable of sustaining them, patronage networks to fund them, and institutions to transmit them across generations. When the Ottoman governing elite, the Tatar Muslim intelligentsia, and the Indo-Muslim aristocracy were dismembered within a single generation, they took with them not merely their titles and estates but the entire ecosystem of high culture they had patronised and participated in. The printing presses fell silent. The journals ceased publication. The networks connecting Cairo, Kazan, Istanbul, and Delhi were severed. What survived was not a diminished civilisation but a civilisation stripped of the infrastructure required to produce new ideas, condemned to recycle, in progressively degraded form, the thinking of the short 19th century.

The question posed in our second essay, Is Modern Islamic Art Even Possible?, becomes legible against this history. Burak Ömer traces the Copernican turn that severed art from its metaphysical grounding, shifting from participation in divine order to self-expression. Yet the deeper problem is not only philosophical but institutional. The infrastructure that once sustained Islamic art as a living tradition – the courts, the endowments, the guilds, the networks of patronage connecting artisans to sovereigns – was precisely what the three catastrophes destroyed. The essay concludes that what is made in remembrance cannot be sold; it can only be witnessed. But witnessing requires communities capable of recognising what they see – communities whose formation is itself an institutional and material problem, not merely a spiritual one.

Syed Naquib Al-Attas understood this. In Muhammad Bin Abdul Majid’s essay, Syed Naquib Al-Attas & the Rectification of Names, we encounter a figure who understood that civilisational renewal must begin with language. It is only with the rectification of names that a people can think clearly about their condition. Al-Attas’ din-madinah-tamaddun framework, linking religion to city to civilisation, was not abstract philosophy but a blueprint for institution-building. ISTAC, his Moorish palace-fortress in Kuala Lumpur, was the embodiment of that vision: an attempt to create a knowledge-producing institution adequate to the scale of the challenge. Political machinations ultimately undid ISTAC, showing that ideas alone cannot sustain themselves. They require political protection, material resources, and coalitions capable of defending them against those who benefit from dysfunction.

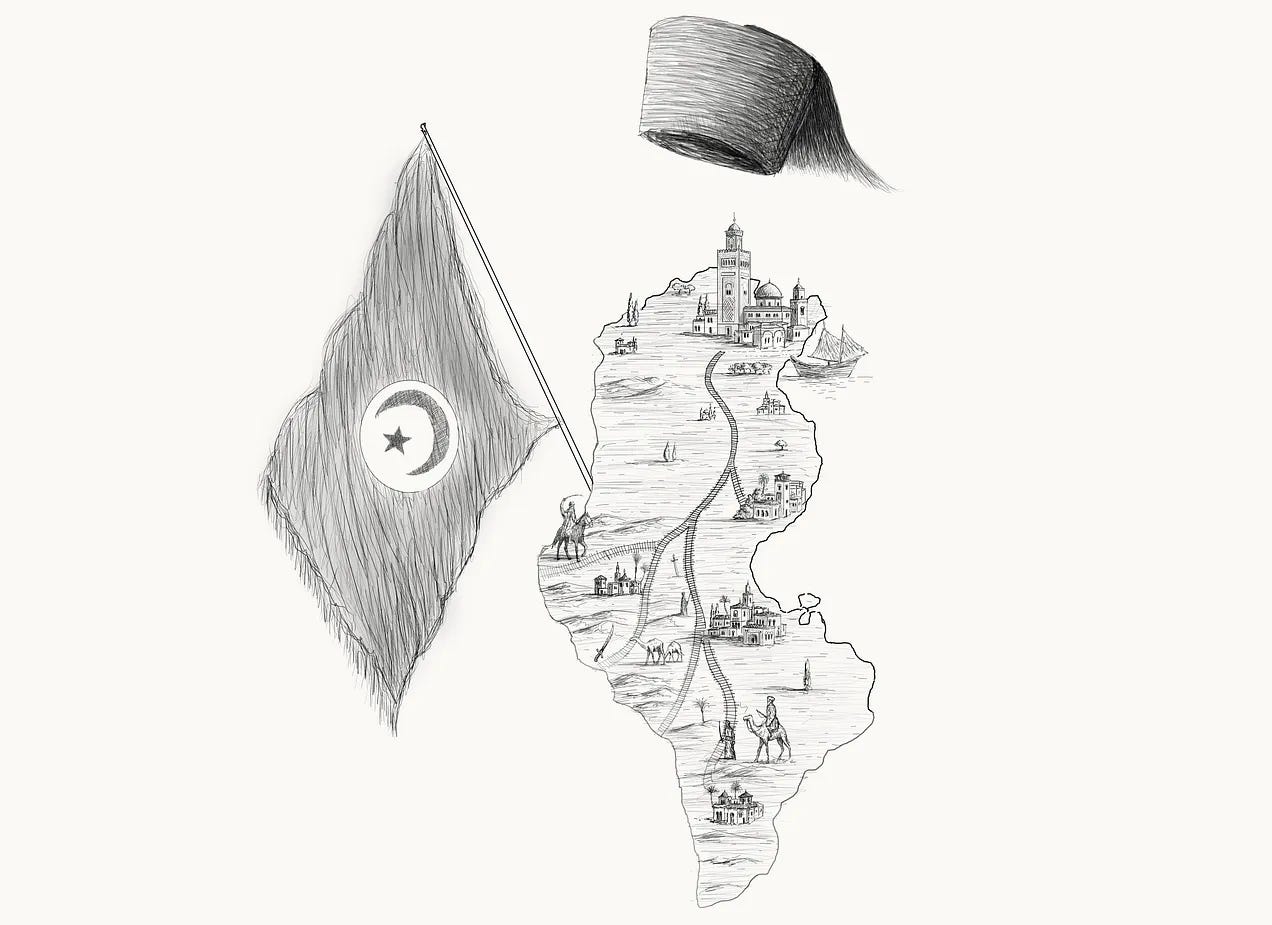

Hayreddin Pasha grasped this a century earlier. In The Life and Lessons of Hayreddin Pasha, Salim Jeridi explores the life of the Circassian mamluk who rose to become Tunisia’s Prime Minister in the 19th century. Hayreddin Pasha understood that justice was the pivot upon which the destiny of nations turned, and his seminal book, Aqwam al-Masalik, remains a masterwork of political economy and a practical guide for statecraft. Hayreddin reformed Tunisia’s agriculture, protected its nascent industries, and founded institutions that would train its elite for decades. Yet he was undone in the end, opposed not only by French imperial interests but also by the court machinations at home, chiefly by his own father-in-law, Mustafa Khaznadar, who systematically sabotaged reform to protect his plunder. Within four years of Hayreddin’s fall from power, French troops had imposed a protectorate.

This pattern of reformers undone by their own compatriots echoes through the recent centuries. Kasurian explored another case study in our Summer issue with Tipu Sultan, whose extraordinary modernisation of Mysore was nullified by his failure to maintain the alliances that might have checked British expansion. Muhammad Ali Pasha’s Egypt nearly reformed the Ottoman world from within before British intervention halted his advance. In each case, the material and intellectual capacity for renewal existed. What failed was the political coalition that might have sustained it.

The Ma Clique offers a different model of agency altogether. Steven Zhou’s account of the Hui Muslim warlords who navigated the collapse of the Qing Dynasty and the chaos of Republican China is a remarkable story of political pragmatism. The Ma families survived and, at times, thrived by accurately reading the balance of power and positioning themselves accordingly. This political intelligence preserved Hui autonomy for decades. Their example reminds us that agency takes many forms, and that survival itself can be a form of resistance when the alternative is annihilation.

We conclude this issue with a diagnosis that extends beyond any particular civilisation. Democracy Will Not Survive the Age of Consumption examines the structural tension between those who produce and those who consume – a tension that, even in mature democracies, increasingly favours the latter. The productive minority, squeezed by extraction from above and below, faces a narrowing set of options: exit, withdrawal, or quiet disengagement. When the consuming majority becomes large enough, no political mechanism can prevent it from voting itself into transfers from the productive minority. This is not a problem unique to any single civilisation. Yet, the fatal conceit of developed democracies is the belief that they possess some innate capacity to evade the repercussions of consumption. What was once a gradual turn is now rapidly culminating in a general crisis of political economy, with no guarantees as to which model or ideology of politics will survive the coming gauntlet.

What to Expect from Kasurian in 2026

Kasurian returns in March 2026 with a new publishing schedule: two issues per year, each comprising twelve essays. The first will run from March through May, the second from September through November.

Until then, we will be hosting salons in London, Toronto, San Francisco, and New York. These gatherings seek to bridge theory and action, past and present, and to bring together those who wish to explore how cultural production, knowledge creation, policymaking, and technology might serve the betterment of civilisation. They are spaces for serious engagement, not just with ideas but with people who are curious about the world, how it works, and how to act on it.

Paid subscribers can expect invitations to the first salons of 2026, to be held in late January, in the coming weeks.

Thank you for reading Kasurian.

Artist: All art has been custom-drawn for Kasurian by Ahmet Faruk Yilmaz. You can find him on Instagram and Twitter/X at @afaruk_yilmaz.

Socials: Follow Kasurian on Substack Notes, Instagram, and Twitter/X for the latest updates.