Syed Naquib Al-Attas & the Rectification of Names

The Malay aristocrat-philosopher’s pursuit of civilisational revival through language.

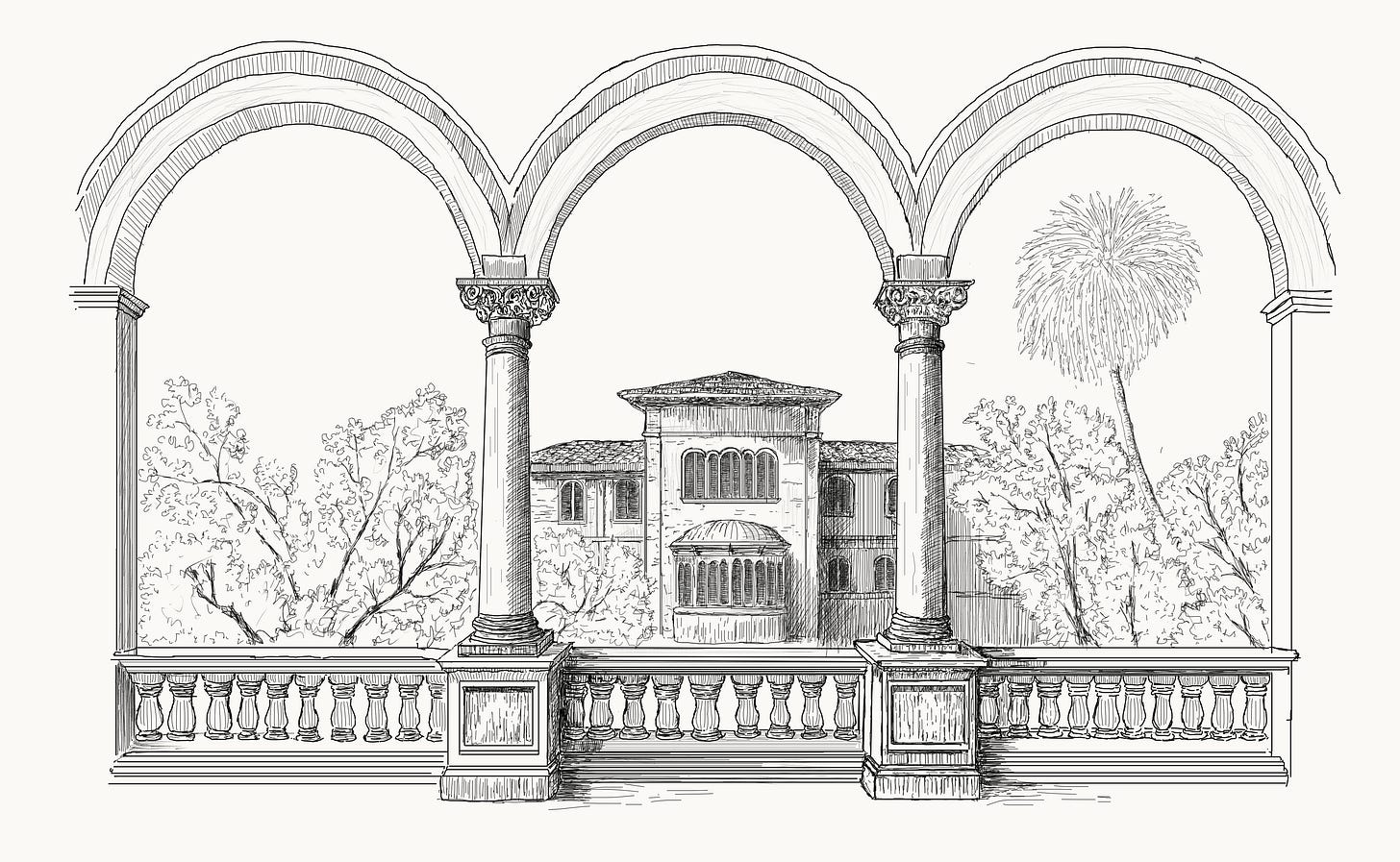

In the beating heart of Kuala Lumpur lies the lush tropical green district of Bukit Tunku, the favourite dwelling of Malaysia’s ultra-elite. Amid their luxury condominiums and villas is a Moorish-styled palace-fortress structure that appears to have been transposed from 15th-century Andalusia into the Malay tropics. The International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilisation (ISTAC), dubbed ‘the beacon on the crest of the hill’, is, to even an untrained eye, an architectural splendour.

Established in 1987, ISTAC marked the beginning of perhaps the most significant intellectual response in the Muslim world to the civilisational decay of the 20th century. It was conceived, both in concept and form, by the prolific writer and polymath, Syed Muhammad Naquib Al-Attas, who was ISTAC’s principal planner, designer, landscaper, and Founder-Director.

Al-Attas was driven by the belief that Islam would flourish as a civilisation through the ordering of meaning through language, both in its material aspects and otherwise. After all, by one measure, the scale of a civilisation is measured in the size and complexity of its knowledge-processing functions and institutions. The relative dearth of indigenous knowledge production in the Muslim world today demands both an explanation for how this state of affairs came to be and a response in the form of new tools, techniques, and forms of organisation that allow for the building of new knowledge-producing systems.

Al-Attas came closest to providing a systematic response to this quandary.

The Youth of Syed Muhammad Naquib Al-Attas

Al-Attas was born on 5 September 1931 and was, by any measure, an elite. A thirty-seventh direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, his genealogical tree spans over a millennium through the House of Ba’Alawi, a family of sayyids (who trace their family lineage to the Prophet) centred in the Yemeni region of Hadhramaut. Al-Attas is also affiliated with the Johore royal family through his maternal grandmother, Ruqayah Hanum, a Turkish aristocrat. His mother, Sharifah Raquan Al-‘Aydarus, hailed from Bogor, Java, and was a descendant of the Sundanese royal family through her maternal side.

As a child, Al-Attas moved between a madrasa in Java and the English school in Johore. In Johore, living with two uncles who served as Johore’s Chief Minister, he was exposed to a collection of rare Malay manuscripts and Western classics. His formative exposure to traditional Islamic sciences, Western classics, and Malay letters formed the pillars that would characterise his lifelong oeuvre.

After completing a period of military training at the Royal Military Academy in Sandhurst, Al-Attas returned to Malaysia and enrolled as an undergraduate student at the University of Malaya. There, he published a book, “Some Aspects of Sufism as Understood and Practised Among the Malays,” which earned him a Canada Council Fellowship for an unprecedented three years of funding to study at McGill University. It was here that he became acquainted with a network of esteemed academics at the frontier of Islamic Studies, including Hamilton Gibb and A.J. Arberry from England, Toshihiko Izutsu from Japan, Seyyed Hossein Nasr from Iran, and Fazlur Rahman from Pakistan.

He then completed his PhD at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London under the supervision of A.J. Arberry and Martin Lings. As one of the first few Malaysians to earn a doctorate, Al-Attas swiftly rose to assume the rank of Dean of the Faculty of Arts at Malaysia’s first university, the University of Malaya. In 1970, he co-founded the National University of Malaysia and shaped its Institute of Malay Language, Literature, and Culture.

Academia and Beyond

On his return from Canada and London, and newly armed with a doctorate and an early scholarly claim, Al-Attas’ influence began to leave visible marks on Malaysian intellectual life. The academic scene of the 1960s and 1970s was a crucible of competing paradigms, each vying for the attention of a small, carefully curated cohort of intelligent, idealistic young Malaysians. In a fledgling, rapidly industrialising nation with a thin Muslim majority and delicate racial (im)balance, Al-Attas’ discourse on Islam, offering a civilisationally rich and intellectually rigorous alternative to both rigid traditionalism and modernist reform, attracted a significant following among university students already agitated by the global tides of Islamic revivalism.

Across the wider Muslim world, the late 20th century was a time of rediscovery and independence. In the Nusantara, as elsewhere, religious currents were broadly split between the Traditionalists (Kaum Tua) and the “Jadidists” (Kaum Muda). The latter, shaped by reformist trends like the Salafi and “Ikhwani” (Muslim Brotherhood) movements, were gaining sway among youth rediscovering and seeking Islam as an all-encompassing worldview.

Al-Attas offered a different route: neither a rupture with tradition nor an uncritical embrace of modernist reform, but rather a rediscovery of Islam’s civilisational depth. For some students, Al-Attas’ discourse represented a dynamic continuity of centuries-old intellectual tradition in a brave new world. Unlike the reformist-modernists of that period, Al-Attas’ creative deployment of the Islamic tradition did not constitute a rupture. He did not call for a return to the Early Generations (salaf) in a way that bypassed the millennium of accumulated, codified and institutionalised knowledge that had followed those generations. And although his high metaphysics remained accessible only to a small group of close students, sociologically, his discourse fostered a self-identity that unapologetically viewed the world through the lens of Islam, one that is thoroughly rooted in Malay culture but confidently outward-looking.

Underlying Al-Attas’ orientation was a deeper source: The view that any civilisational renewal begins with language and the conceptual architecture it sustains.

Language, Thought, Civilisation

Where many foreground Islam’s millennial-old history through its sociopolitical and economic dimensions, Al-Attas is distinct in his emphasis on language above all, in this case the Arabic of the Quran, as the primary engine of Islam’s civilisational arc.

The clarity of Quranic Arabic is a remarkable characteristic of the Arabic language itself. Built on trilateral ‘roots,’ and governed by a disciplined semantic structure, Arabic gives each word a defined, finite, and stable conceptual range. This structure enabled Muslim lexicologists, who worked continuously for more than a thousand years, to produce precise, systematic, and scientific lexicons. This stability of meaning means that Quranic Arabic, unlike all other languages, allows objective truth to be conveyed across time and space, regardless of period, geography or circumstances.

Arabic, Al-Attas argues, was chosen to be the language of the Quran because of its inherent clarity. In contrast to the Graeco-Roman or Irano-Persian languages that dominated the region at the time of revelation, Arabic was not burdened with the baggage of mythological vocabularies. Instead, Arabic was a pristine language that could express ideas with precision. This linguistic economy enabled Islam to spread rapidly in the coming centuries, expressing an all-encompassing worldview that attracted adherents not only among Arabs and other Semites but also among Persians, Egyptians, Berbers, Europeans, Africans, Indians, Chinese, Turks, and Malays.

The nimble and precise economy of Islam’s linguistic and conceptual world proved decisive in the Nusantara, where the then still modest Malay language was deliberately and strategically chosen to be the vehicle for Islam’s spread. Unlike Old Javanese, the region’s dominant literary language, the underdeveloped Malay language was free of elaborate Hind-Buddhist terms drawn from ornate religious epics. Early proponents of Islam’s spread in the region gradually incorporated key Arabic terms into Malay, creating an interlacing network of meanings, i.e., a ‘semantic field’. This semantic field came to constitute a novel worldview. Clear prose was employed on matters of creed, and poetry was always accompanied by sober, systematic commentaries. As it did for the Arabs, Islam’s ascension marked a momentous shift in the Malay adoption of the Arabic script, transitioning from a largely oral literary tradition to a written literary culture among the Malays.

Din (Religion) – Madinah (City) – Tamaddun (Civilisation)

The transition from an oral tradition to a rich, written intellectual culture reveals a deeper civilisational logic that animates the Muslim worldview. Al-Attas captures this logic in the interlaced concepts of Din (religion), Madinah (City) and Tamaddun (Civilisation).

In English, the word “religion” originates from the Latin word “religio,” meaning the bond between man and the gods. The English ‘religion’ reveals little about what this bond is and how it should be acted upon. Left ambiguous, it opened the door to shifting, subjective interpretations. This ambiguity has shaped the turbulent path of Western religious history. By contrast, the Qur’anic din – the usual translation for religion – is rooted in the trilateral D-Y-N. It is directly linked to dayn, or debt. Like all debts, including the greatest debt of all — the debt of life and existence bestowed on man by God — is best discharged within an organised society equipped with law and ordinances governing debts, their disposition and the related networks of commercial life.

In other words, debts are best discharged in towns and cities. The social order is expressed in the madinah, derived from the verb maddana, from which another term of significance is also derived, tamaddun, or civilisation.

It was no coincidence that when the Prophet ﷺ arrived in the city of Yathrib, it was renamed to Al-Madinah, The City. It was here that Muslims were gradually taught and learned how to fulfil their fundamental duty of existence to God. The Hijrah, the historic emigration to Al-Madinah, also marked the beginning of the Islamic calendar (Hijri).

Drawing on the French historian of ideas Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges, Al-Attas notes that the Greek polis (city) never became universal because it lacked the concept of a Universal God. The madinah, however, is founded on din which originates from that Primordial Covenant where mankind had collectively affirmed God’s Lordship – “Yes, indeed we witnessed” (al-A’raf (7): 172). A universal bond is thus built into din and madinah, the idea of a cosmopolis intrinsic in their unity.

For over a millennium, Muslims did not need to theorise or elucidate the connection between din, madinah, and tamaddun because they lived it. The man of din was a man of civilisation, and this relationship was not mere speculative philosophy. Even at the peak of spiritual experience, during the Mi’raj and his direct audience with God, the Prophet ﷺ returned to his city to continue the civilisational work of Islam. It is the Believer’s obligation, by virtue of his belief, to self-identify, think, act, and aspire at the scale of civilisation.

ISTAC was Al-Attas’ first step in embodying this system of thought in the form of an enduring institution.

ISTAC: the Beacon on the Crest of the Hill

“Remember that we are a people neither accustomed nor permitted to lose hope and confidence, so that it is not possible for us simply to wrangle among ourselves and rave about empty slogans and negative activism while letting the real challenge of the age engulf us without positive resistance. The real challenge is intellectual in nature, and the positive resistance must be mounted from the fortification not merely of political power, but of power that is founded upon right knowledge.”

— Al-Attas, in his Islam, Secularism, and the Philosophy of the Future (1978)

This conceptual architecture between din and tamaddun demanded an institutional expression, and it soon met with the politics of those attempting similar projects.

After the First World War, the old transnational networks of Muslim elites were abruptly dismembered, taking with them the power, patronage, and high culture crucial for the production of knowledge. Into this vacuum, the Islamic revivalist movements of the late 20th century prioritised mass mobilisation. Their aim was pragmatic: to win electoral power through democratic means and implement sharia via the nation-state.

Al-Attas rejected this zeitgeist, arguing against the reductive sloganeering of sharia into mere jurisprudence. Any genuine civilisational revival had to begin at the level of knowledge, and inside its most decisive institution: the university.

The university traced its origins to medieval times, revealing parallels with the Islamic learning institutions of that era, such as the bayt al-hikmah (library), the Sufi zawiyah (lodges), and the madrasah (colleges). For Al-Attas, these institutions, physically centred around the mosque, reflect the proper hierarchy of knowledge – a circle with the knowledge of the universals (i.e., devotional sciences, astronomy) at its epicentre, from which expands other knowledge of particular benefits (i.e., medicine) to man and society, with respect to his anatomical faculty. Civilisational renewal required restoring that Centre and the teleology it carried.

Al-Attas presented this argument at the First World Conference on Muslim Education, held in Mecca in 1977. He entrusted Ismail R. Al-Faruqi, Palestinian-American Muslim scholar with a rare expertise in Christian ethics and comparative religion studies, with a manuscript containing his conceptualisation of the Islamic university, which he intended to publish as a book. This exchange would later prove consequential.

The friendship between Al-Attas and Al-Faruqi blossomed in the early 1960s. In 1974, Al-Attas invited Al-Faruqi to Malaysia for a series of lectures and introduced him to local Muslim intellectuals, including one Anwar Ibrahim, the President of Angkatan Belia Islam Malaysia, or the ‘Malaysian Islamic Youth Movement’ (ABIM). Al-Faruqi later hosted Al-Attas at Temple University as a Visiting Professor and arranged for him to keynote a major symposium of the Association of Muslim Social Scientists. The lecture was widely lauded. Al-Faruqi even wrote to say Al-Attas had become “the raison d’être” of the organisation:

“Your colleagues, members of the Executive Board and the large number of fellow Muslims asked to comment on your performance at the convention–all were proud of you…You are the AMSS. Your performance, i.e., your stimulation of Islamic thinking and your contribution to the legacy of thought, is its raison d’être and end. I hope this realisation has dawned upon you with the same bright intensity with which it did upon the AMSS Executive Boards of the last five years.”

However, cracks in their relationship soon began to appear. At Al-Faruqi’s request, Al-Attas wrote a 40,000-word manuscript, “Dialogue with Secularism”, and submitted it to Al-Faruqi for publication. Al Attas’s inquiries about its fate went unanswered. He began to believe his ideas were circulating without attribution and in “vulgar forms.” Al-Attas soon published it as part of his seminal work, Islam, Secularism, and the Philosophy of the Future, under ABIM’s publication, where he also issued a pointed warning in the preface about the damage done “by plagiarists and pretenders.”

The intellectual fallout was fundamental, revealing not only a breach of personal trust but a deep fracture in his vision versus Al-Faruqi’s, for whom the Islamisation of knowledge in concrete terms meant “to Islamise the disciplines, or better, to produce university-level textbooks recasting twenty disciplines in accordance with Islamic visions.” Essentially, Al-Faruqi wanted to rewrite modern disciplines into “Islamic” textbooks.

Al-Attas believed this was superficial. For him, knowledge rests on vocabulary, and without rectifying the key terms that shape the Muslim worldview, ‘Islamisation’ would collapse into textbooks padded with Quranic quotations but stripped of conceptual integrity. Without reorienting the very structure of the university to reflect man in his entirety, or reinstating the various disciplines of knowledge back into their proper hierarchy, the confusion and error in knowledge beleaguering the Muslim mind will not be rectified, posing a stumbling block for frontier knowledge production.

The divide soon took institutional form. In 1982, at the Organisation of Islamic Countries (OIC) meeting between Muslim heads of state, Malaysia’s Prime Minister, Mahathir Mohamed, proposed an international university dedicated to the integration of knowledge. Although modern universities in Muslim countries have long offered both religious and ‘secular’ sciences, what was new with Mahathir’s suggestion was that this new university was to be explicitly founded with the idea of ‘integration’ of knowledge. It was clear that this would be predicated on Al-Faruqi's exposition in his book, Islamisation of Knowledge, a term that, for Al-Attas, was misappropriated from his original work.

Backed by eight Muslim countries, the International Islamic University of Malaysia (IIUM) was established the following year. Al-Faruqi’s prominent role as the co-founder of the globally influential, US-based International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT) and his close relationship with Mahathir meant that the IIUM, despite being based in Al-Attas’ native country, would reflect Al-Faruqi’s conceptualisation closer than that of Al-Attas.

However, in 1987, Al-Attas received the closest thing to a carte blanche to actualise his own vision. His long cultivation of students and young intellectuals had borne unexpected fruit: Anwar Ibrahim, once President of ABIM and perhaps Al-Attas’ most famed protégé, had rapidly risen in Malaysian politics. At its peak, ABIM, steered by the charismatic Anwar (whose influence led to ABIM being called the Anwar Bin Ibrahim Movement in jest), rode the wave of global Islamic revivalism and the rise of a new Malay Muslim middle class created by affirmative-action policies. Together, these forces made ABIM more influential in shaping public discourse.

When Anwar decided to join the ruling party led by Mahathir in 1982, one of the most significant political unions in Malaysian history was forged —a union initially brokered by Al-Faruqi. Once inside the establishment, Anwar used his successive ministerial positions to advance a broad Islamisation agenda, from developing an Islamic finance sector to embedding Islam in the state bureaucracy and education system. After becoming Minister of Education in 1986, he moved to establish ISTAC with Al-Attas as its Founder-Director. Although ISTAC was not technically a full, standalone university, it would operate as an autonomous institute under the IIUM.

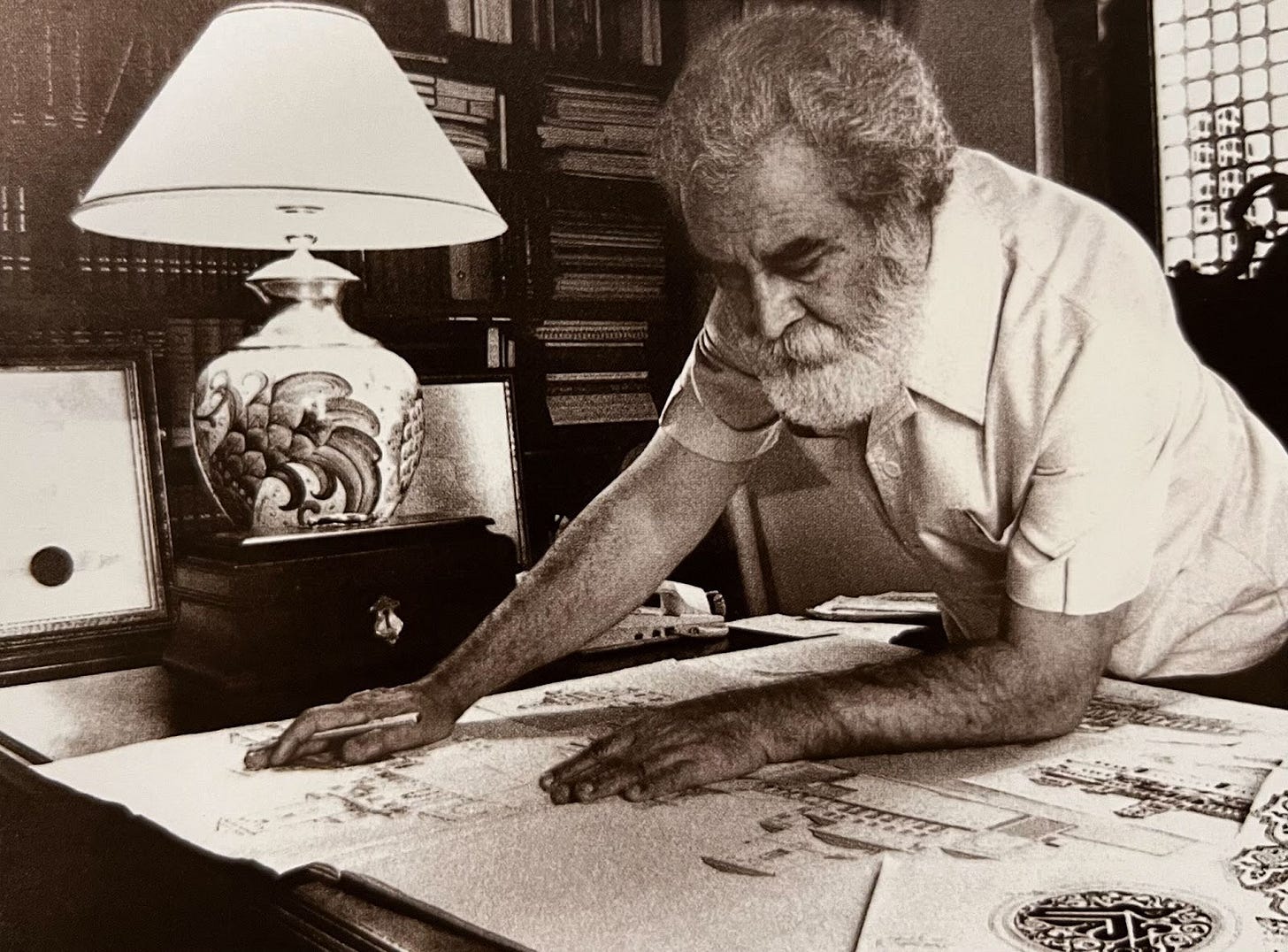

ISTAC’s groundbreaking ceremony took place on a Friday, 22 February 1990, in honour of the Prophet’s Ascension, the Mi’raj. Al-Attas, despite receiving no formal training in architecture, shaped virtually every aspect of ISTAC’s material construction. ISTAC Illuminated: A Pictorial Tour makes this unmistakable, showcasing Al-Attas’ own sketches, from the muqarnas suspended from the ceiling to the fountain bowl in the main courtyard. Through Al-Attas’ eye, one sees the vision of the high culture of Islamic civilisation that he hoped to revive, with ISTAC at its epicentre.

In 1997, just a decade after ISTAC’s establishment, Malaysia was jolted by the sacking of Anwar, then Malaysia’s Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister. The two highest-ranking officers in Malaysia’s government, Mahathir and his deputy Anwar, had a fallout over the handling of the Asian Financial Crisis. Anwar favoured fiscal discipline to calm capital markets, whereas Mahathir preferred strong fiscal support and decisive capital control to shun speculators. What began as a technocratic disagreement soon turned into personal bitterness – a clash that still casts its shadow over the country to this day. On 20 September 1998, Anwar Ibrahim was arrested under the Internal Security Act.

While the rest of Malaysia grappled with the fallout from Mahathir and Anwar’s impact on Malaysia’s politics and economy, Al-Attas’ rivals in academia and government, who had long envied Al-Attas’ ostensibly privileged position within the administration, began to orchestrate their own coup. Anwar’s incarceration was soon followed by a clean wipeout of his supporters from key positions. Al-Attas was not spared. Mahathir, who was the first Prime Minister to not have come from an aristocratic background and who was also ideologically more aligned with the modernist tendencies of Al-Faruqi, felt no sympathy for Al-Attas or his cause. In 2002, Al-Attas was expelled from ISTAC, and the institution lost its autonomous status.

In a mere decade, ISTAC, notwithstanding its strict curation of students, had produced graduates including Ibrahim Kalin, the current Director of Turkey’s National Intelligence Organisation, and Mustafa Ceric, the former Grand Mufti of Bosnia. ISTAC had produced critical monographs on the elemental, immaterial building blocks of Islamic civilisation – such as the concept of education, the philosophy of science, and the psychology of the human soul – which were translated into Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Chinese, Russian, and Bosnian. It had attracted prominent admirers, including Annemarie Schimmel, Syed Hossein Nasr, Javed Iqbal, and a young Hamza Yusuf, who went on to found Zaytuna College in the US.

Reflections and Lessons for the 21st Century

Al-Attas’ lifelong oeuvre, including but extending beyond ISTAC, leaves much to be reflected on. His din-madinah-tamaddun framing sought liberation from the contemporary secular taxonomy of religion, affirming Islam as simultaneously a religion and a civilisation. Islam is deeply personal, metaphysical, and psychological; Islam is thoroughly social, cultural, and civilisational. Islam centres around the sacred; Islam extends to the profane. Muslims cannot seriously proclaim to be Muslims without aspiring to affect positive change in urban life, and on the frontier, universal issues facing humanity.

Because our din, the bond of debt between God and man, is based on that Primordial Covenant which we collectively undertook, whether one chooses to submit to it or otherwise, it is incumbent on Muslims, who do believe that the Covenant did indeed take place, to contribute to solving issues facing humanity writ large. Moral and material issues facing humanity – such as ecological rupture, demographic shifts, the mental health epidemic, and gaping inequality in the face of unprecedented abundance – ought to be at the front and centre of Muslims’ discourse.

To achieve this, Muslims must understand not just the intellectual genesis and cultural values underpinning this milieu (which Al-Attas had elucidated in his Islam and Secularism), but also the material realities that have dislodged and radically altered the world in the past three centuries. In a world that has never been more interconnected, Muslim thinkers and institutions at the forefront of knowledge production ought to have a profound understanding of the base layer shaping the world – for example, the infrastructure of the world’s energy and financial systems, industrial production, trade, geopolitics, demographic shifts, and ecological limits.

Frontier thinkers cannot afford to be confined within the silo of Islamic Studies. Al-Attas’ ‘Islamisation of knowledge’ project was not meant to make Muslims tribal and provincial. To reduce Al-Attas’ ideas into pointers for the finer details of theological disputes or political quibbles, by paraphrasing Al-Attas without substantive contextualisation of his ideas, is to render great injustice to his legacy.

To propel Muslims who are still “floundering in a sea of bewilderment and self-doubt”, Al-Attas equipped us with the confidence in our vocabularies, reinterpreted in light of our present circumstances, yet firmly rooted in Revelation, for us to be able to look outside and sieve, re-sieve, and thus receive the best from what others have to offer – to venture with curiosity and conviction.

Beyond his corpus, at an institutional level, Al-Attas’ strategy also offers lessons for any 21st-century attempt at civilisational revival. Ahead of his time, he identified the frontier of knowledge-producing institutions as a key priority for civilisational revival. Yet, Al-Attas also conceded that the operationalisation of the Islamic university that he conceptualised would inevitably be experimental, requiring rigorous trials and correction of errors. One must adopt a longue durée view of civilisational change in solving a problem of this magnitude.

Al-Attas’ conceptualisation of an Islamic university seeks to restore the university’s abiding centre as reflected by the individual self, which would hold together the unity of knowledge and make clear the final aim of its pursuits. Specialisations that occur in this setting will reflect these values. That said, it is now starkly clear that what differentiates the past three centuries was not just niche innovations at the frontier of knowledge. The systematic application of these innovations in the manipulation of nature and society at an industrial scale has increasingly entrenched us in what Marshall Hodgson calls a ‘technicalistic’ society.

Even in the optimistic event that an Islamic university, in the sense Al-Attas envisioned, is established to reinstate the proper hierarchy of knowledge, Muslims can only pragmatically affect change at the level of humanity if this worldview is actualised at the material level on a greater scale.

What forms of institutional arrangements must Muslims imagine to achieve this? How do we fund, sustain, and scale these institutions? Should we still rely on the apparatus of the nation-state in the way that ISTAC did? Should visionaries such as Al-Attas be given a position in the government, similar to Wang Huning in the Chinese government, to ensure vision endurance? Should we instead reinvigorate that lost transnational network of elite Muslims? If so, what institutions are needed to recreate a respectable high culture such that Muslim elites are willing to band together? These are tough questions with no easy answers, but they are certainly crucial for any serious 21st-century attempt at civilisational revival.

Al-Attas is now 94 years old, having published what was probably his last book, Islam: the Covenants Fulfilled, two years prior. While no single person could be expected to provide a panacea for our predicament, Al-Attas undoubtedly paved the path forward.

“They are like torches that light the way along difficult paths; when we have such torches to light our way, of what use are mere candles?”

Author: Muhammad Bin Abdul Majid served as a policy economist in the Malaysian federal government before pivoting into strategy at one of Southeast Asia’s leading tech firms. He is based in Kuala Lumpur.

Socials: Follow Kasurian on social media via Substack Notes, Instagram, and Twitter/X for the latest updates.

Further Reading:

Islam, Secularism, and the Philosophy of the Future, Syed Muhammad Naquib Al-Attas

The Concept of Education, Syed Muhammad Naquib Al-Attas

Islam: The Covenants Fulfilled, Syed Muhammad Naquib Al-Attas

Preliminary Statement on a General Theory of the Islamization of the Malay Archipelago, Syed Muhammad Naquib Al-Attas

ISTAC Illuminated: A Pictorial Tour, Sharifah Shifa Al-Attas

The Origins of Malay Nationalism, William Roff

Islamic Revivalism in Malaysia: Dakwah among the Students, Zainah Anwar

The Educational Philosophy and Practice of Syed Muhammad Naquib Al-Attas: An Exposition of the Original Concept of Islamization, Wan Mohd Nor Wan Daud

Islamization of Knowledge, Ismail Al-Faruqi and Abdul Hamid Abu Sulayman