How the Mongols Revived Islamic Civilisation

The Mongol invasions are blamed for Islamic civilisation's long decline. Is our understanding of history wrong?

Reconsidering the Mongols

By the mid-13th century, the last Crusader strongholds had been swept out of the Levant. The Christian conquest of Jerusalem in 1099 had marked the high tide of European ambition in the Middle East, but the Crusaders held the holy city for less than a century before Muslims reclaimed it.

The Crusades were the most serious challenge Islamic civilisation had yet faced and had triggered an extraordinary period of dynamism that forced Muslims to contend with, for the first time, the question of civilisational renewal. It would not be the last time. Even as the sun set on the western threat, a new storm that would transform the very foundations of Islamic civilisation was gathering in the east.

The Mongols were coming.

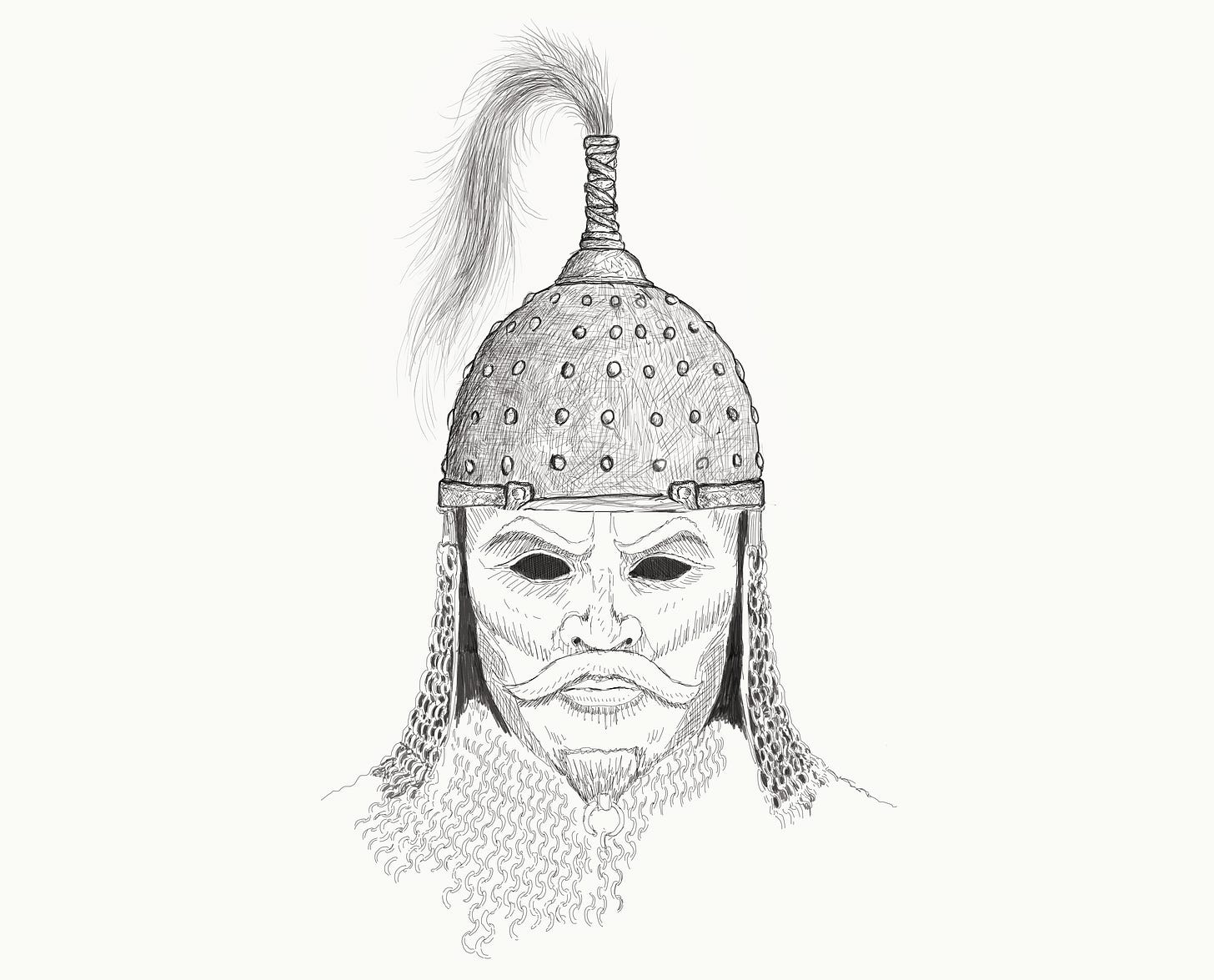

Referred to as Tatars by Muslim and Christian contemporaries, these new conquerors were likened to the eschatological Yajuj wa Majuj, a not-quite-human race of devourers that would drink the sea and blot out the sun. Today, in popular memory the Mongol invasions are synonymous with biblical-scale bloodshed, destruction, and plunder. Stories of ‘rivers of blood and ink flowing through the River Tigris’ embody these memories, describing the brutal destruction of a culture, way of life, and civilisation.

In classical Orientalist history, the Mongol invasions are presented as the catalyst for Islam’s “long decline,” an enormously influential thesis that has been internalised in the popular Muslim consciousness. According to this theory, the Abbasid era’s ‘Golden Age’ saw the flourishing of culture and knowledge, including science, philosophy, and the arts. The Mongols, with their devastating sack of the Abbasid capital of Baghdad, the heart of the Golden Age, delivered the material deathblow to this once-vibrant civilisation, creating the conditions for centuries of material and intellectual decline.

This theory is almost entirely wrong. When Hulagu besieged Baghdad, he did not encounter the grand city of One Thousand and One Nights, but a shadow of its former glory. There was little to loot and hardly enough books to turn the Tigris black with ink. Claims of large-scale library destruction appear only in later sources, emerging in the early 15th century and gaining popularity as historians repeated them. The Mongols were not the executioners of the fabled Islamic Golden Age, nor were their invasions the reason for Islam’s long decline in the centuries thereafter. Instead, the aftermath of the Mongol invasions would provoke a systematic re-adjustment of Islamic civilisation as its gravitational centres migrated beyond the ‘classical heartlands’ of Iraq and Syria, and within a few centuries would reach its greatest extent yet.

The Scourge of God

The Mongols were the last steppe people to emerge from the great Eurasian ‘conveyor belt’ of invasion, a millennia-old phenomenon that had periodically unleashed nomadic conquerors to assail the sedentary civilisations of China, the Middle East, and Europe. Like the Xiongnu, Huns, and Göktürks before them, the Mongols employed similar expansion strategies and military tactics to force settled societies into submission. But the Mongols were different. Their extraordinary speed, vast territorial reach, and sheer military prowess made them the most formidable threat to emerge out of the steppe.

In 1218, the Fifth Crusade laid siege to the Egyptian port of Damietta. Both the Crusade and siege would end in yet another dismal failure just a few years later. In the same year, Chinggis Khan stood at the eastern frontiers of the Muslim world and delivered an ultimatum to the Shah of the Khwarazmian Empire, Muhammad II: submit to vassalage or face annihilation. Chinggis’ ultimatum was said to be delivered in response to the actions of Inalchuq, the Khwarazmian governor of the city of Otrar, who had executed an entire Mongolian trade caravan which included a Mongol envoy. Chinggis reportedly demanded that Mahmud hold Inalchuq to account before his ultimatum. In any case, it provided the perfect pretext: Mahmud rejected Chinggis’ ultimatum, who in response unleashed a brutal campaign that within a few years swept across cities of Bukhara, Samarkand, Nishapur, and Merv. Muhammad survived the invasion by fleeing to the Caspian Sea. According to most accounts, he died in exile. Inalchuq was captured by the Mongols, who executed him by pouring molten silver into his eyes and ears.

A few years after Chinggis died in 1229, the Mongols, now led by Chinggis’s son Ogedei, resumed their expansion westward. By the 1240s, they had already conquered much of Persia and its neighbouring regions. They then defeated the Seljuks in Anatolia, reducing them to a client state, and launched a series of raids into Syria and parts of modern-day Iraq. The most devastating blow came to the Muslims in 1258: Chinggis’ grandson Hulagu sacked Baghdad, decimated its population, and executed the recalcitrant Caliph Al-Musta’sim by rolling him up in a carpet and having him trampled by horses, following Mongol tradition. This event effectively brought the Abbasid’s 500-year rule to an end.

The scale of devastation sent shockwaves throughout the Muslim world, fueling accounts of unimaginable brutality. Medieval chronicles detailed the millions of casualties and recounted the Mongols’ gruesome and creative methods of execution. To modern readers, the accounts may seem exaggerated; to Christian and Muslim contemporaries, however, the Mongols may as well have risen from the darkest crevices of Tartarus. No story was too outlandish. As they swept throughout the land, the Mongols were seen as a physical manifestation of God's wrath. The notion survives to this day in the oft-cited (though apocryphal) saying of Chinggis himself:

“I am the Scourge of God...If you had not committed great sins, He would not have sent a punishment like me upon you.”

The sense of doom was inescapable. Messianic movements gained traction, with sightings of comets, earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions quickly being interpreted as ill omens. Meanwhile, the Mongols launched full-scale incursions into the Levant aiming to push into Egypt and from there, into the very heartland of Islam, the Arabian Peninsula. For a time, it seemed that nothing could stop the Mongols from bringing the whole world to the brink of destruction and fulfilling their role in the apocalyptic prophecy. And yet, the Mongol invasions faltered just as Islamic civilisation seemed on the brink of destruction.

After Baghdad, Hulagu sacked Damascus and began preparations to invade Egypt. He sent envoys to Cairo, the capital of the Mamluk state in Egypt and the last remaining sovereign Muslim polity outside of North Africa, demanding their surrender to the Mongols. The Mamluk Sultan Sayf Al-Din Qutuz responded by executing the envoys and displaying their heads on the gates of Cairo. Qutuz mobilised the Mamluk armies, preparing for a showdown with Hulagu. It was at this moment that history turned. In 1259, the death of then-Mongol ruler Möngke Khan forced Hulagu to leave the Middle East with much of his army and return to Mongolia to attend the Kurultai and appoint a successor. Hulagu appointed one of his subordinates, Kitbuqa, in his stead with a much-reduced fighting force.

A year later in 1260, at the battle of ‘Ain Jalut, the Mamluks would inflict the first defeat the Mongols had ever faced, killing Kitbuqa and decimating his army. Hulagu’s departure was likely the biggest reason for this defeat. It also helped the Mamluks that as distant cousins of the Mongols, they were familiar with steppe cavalry-based warfare, and were not caught off-guard by Mongol military tactics.

Hulagu returned to the Middle East in 1262 to avenge the Mongol defeat at ‘Ain Jalut, but instead became preoccupied with dealing with a new threat: his cousin, Berke Khan, ruler of the Golden Horde, had converted to Islam. Berke, outraged at Hulagu’s sacking of Baghdad and the killing of the Caliph, allied himself with the Mamluks and declared war on Hulagu. Hulagu died in 1265 while on campaign against the Golden Horde.

After 1260, sporadic Mongol attempts to invade Mamluk Egypt continued, but they never succeeded. The tides were already turning. The Mamluk victory at ‘Ain Jalut and Berke’s conversion to Islam heralded a wider shift that would transform the Mongol empire.

Pax Mongolica

“Eighty years elapsed from the time Hülegü Khan’s forces arrived in Baghdad, till the death of Sultan Abu Sa’id. During this period, the kingdom of Iran had a rest from the oppression of men of violence, particularly in the days of the Sultanates of Ghazan Khan, Öljaitü Khudabandah and Abu Sa’id Bahadur Khan. How can anyone describe how well the affairs of the kingdom of Iran were regulated during these three reigns?”

— Auliya Allah Amuli, Tarikh-i Ruyan

Much of the historiography on the Mongol invasions is revisionist, often portraying one side to what is otherwise a complicated story. Muslim reactions to Mongol expansion varied greatly between regions. In eastern Turkestan, the Qara Khitai welcomed Chinggisid forces as liberators from the oppressive rule of Kuchlug, a Christian Mongol warlord who had terrorised the local Muslims. Hulagu’s sacking of the Ismaili fortress-city of Alamut had unexpected consequences, such as the freeing of prominent intellectuals like Nasir al-Din Tusi, who would later serve as Hulagu’s advisor. With Hulagu’s patronage, Tusi would head the Maragheh observatory, housing a treasure trove of texts on medicine, astronomy, mathematics, and philosophy. Contrary to later historians’ claims of Hulagu obliterating all the houses of knowledge and their contents, many manuscripts were relocated rather than destroyed, ensuring their survival.

The Mongols also understood the power of fear. They deliberately exaggerated accounts of their atrocities as a psychological weapon to compel surrender without a fight. Contrary to images of senseless destruction, their violence was methodical and calculated. They usually spared artisans and craftsmen—metalworkers, weavers, manuscript illuminators, ceramicists, glassblowers, jewellers, and calligraphers–and used both flattery and coercion to goad them to Mongol-controlled cities.

Some Mongol rulers showed great sympathy towards Islam. Möngke Khan—rumoured to favour Muslims above all other religious groups—provided tax exemptions for religious officials and institutions. Similarly, Khubilay Khan adopted contemporary Islamic administrative practices and appointed Muslims to high positions in his administration. The Mongols believed that all faiths were legitimate expressions of one Divine Truth and, as such, did not seek to convert their Muslim, Christian, or Buddhist subjects to Tengriism. As Möngke declared to Franciscan friar William of Rubruck: “We Mongols believe in one God, by Whom we live and die... Just as God gave different fingers to the hand so has He given different ways to men.”

While Mongols were feared for their destruction, their rule also brought about a period of stability known as the Pax Mongolica, where Mongol-ruled territories provided a relatively peaceful expanse of commercial and cultural exchange between Europe, the Middle East, Central Asia, India, and China. Cities like Baghdad, Tabriz, Samarkand, and Bukhara, once devastated by conquest, gradually regained some of their former glory as key nodes in this vast network. Muslim merchants, artisans, and scholars moved freely within these networks, expanding the footprint of Islamic civilisation into new territories.

The Ilkhanids, seeking to legitimise their rule among locals, developed a new aesthetic that combined Iranian, Mongol and Chinese artistic traditions. Under Mongol patronage, this unique artistic style would be used to illustrate the Great Mongol Shahnameh and Rashid ad-Din’s Jami' al-Tawarikh, leaving a lasting influence on Persian miniature tradition for centuries to come. Architectural complexes like Takht-e Soleyman, built as an Ilkhanid summer palace atop the ruins of a Zoroastrian temple, were adorned with Buddhist, Chinese, Islamic, and pre-Islamic Iranian motifs. The administrative acumen of the Persians was indispensable to the structure and operations of the Ilkhanate. It was the Mongol ruling elites, along with their Persian administrators, who replaced Arabic with Persian as the main language of court, culture, and historiography, and revived the Persian concept of Eranshahr. All political concepts of ‘Iran’ from later periods to the present day were directly derived from their Mongolian-influenced interpretations. None of this would have been possible without Muslim reciprocity.

For all the mythologising stories of the Mongol devastation, many Muslims benefited greatly from Mongol tolerance. The Mongols provided new opportunities for trade, proselytisation, and power, all of which many Muslims eagerly took advantage of.

Islam’s Response to the Mongol Challenge

“What event or circumstance in these times has been more important than the beginning of the reign of Chingīz Khān, to be able to designate a new epoch?”

— Rashid-ad-Din

The greatness of a civilisation is measured not by the absence of challenges, but by its capacity to identify, respond, and adapt to them. Injecting dynamism into the otherwise staid ‘rise and decline’ theory, British historian Arnold Toynbee proposed a further dynamic of ‘challenge and response’. For Toynbee, civilisations do not simply rise and decline in inevitable cycles but succeed or fail based on their creative responses to existential challenges. These challenges, whether environmental, political, or cultural, serve as catalysts that either dismantle a civilisation or elevate it to greater heights.

The Mongol invasion posed one of the greatest existential threats in Islamic history, yet the Muslim response was neither to languish in subjugation nor treat the Mongols as an aberration to the Muslim body. Instead, the response was to expand the frontiers of Islamic civilisation and integrate the Mongols into it. Sufi missionaries, jurists, traders, viziers, and merchants proactively engaged within the new routes of power, patronage, and trade that their new Mongol overlords provided. Rather than resisting Mongol rule outright, they reshaped it from within.

This process of integrating the Mongols into the cultural and political landscapes of their subjects laid the groundwork for later conversions. Less than fifty years after the sacking of Baghdad, Ghazan Khan of the Ilkhanate announced his conversion to Islam and declared it a state religion, prompting many Mongol elites and troops to follow his lead. In the Golden Horde, Öz Beg Khan, reportedly influenced by Sufi missionary works, converted to Islam. The Islamisation of the western and eastern sides of the Chagatai Khanate followed suit, with the west, such as Transoxiana, increasingly adopting Islam as the ruling elite institutionalised the faith at the state level. Meanwhile, in the east, Islam spread through political alliances, the Sufi missionaries, traders, and local rulers, who sought to strengthen their political legitimacy by aligning with the dominant faith of the populace.

The Seljuks provided the initial blueprint for this integration: like the Mongols, they hailed from the steppe and practised a similar faith before gradually converting to Islam. Here again, the Muslim leadership took a pragmatic approach. Instead of demanding unwavering commitment to the Shari’a among the newly-converting Mongols outright, as long as the overall trend of conversion pointed towards orthodoxy, they tolerated syncretic practices among elites to weaken Shaman and Buddhist influence in royal courts. Islamisation unfolded gradually over decades and generations. Mongols at all levels of society continued ancestral veneration practices and followed the Yasa (law code) established by Chinggis Khan with as much devotion (if not more) as they did the Shari’a. Muslim missionaries, recognising that asking Mongols to abandon deeply rooted practices would likely result in resistance, saw this syncretism as a necessary transitional phase toward normative Sunni Islam. Today, the vast majority of the Mongol descendants who converted to Islam are of the Hanafi school of jurisprudence, and Maturidi school of theology.

In regions with substantial Turkic populations such as the Golden Horde and Chagatai Khanate, Islamisation was naturally accompanied by Turkicisation. A minority ruling class from the start, the Mongols gradually assimilated and absorbed the influences, customs, and languages of the Turkic majority they ruled. Shared cultural and societal traits smoothed the transition. After the Mongols were defeated at ‘Ain Jalut in 1260, subsequent confrontations between the Ilkhanids and the Mamluks led many Mongol soldiers and commanders to defect to the Mamluks. After converting, Mongol defectors were welcomed and often assumed prominent military positions within the Mamluk establishment.

However, conversion was not without political ramifications. As mentioned, Berke Khan, grandson of Chinggis and ruler of the Golden Horde, adopted Islam and clashed with the Buddhist rulers of the Ilkhanate, leading to prolonged military conflict. Ahmad Tegüder, the first Ilkhanate Muslim ruler, was overthrown by his Buddhist nephew Arghun after his swift implementation of Islamic reforms, abandonment of traditional Mongol practices, and diplomatic overtures to the Mamluks. Tamarishin Khan of the Chagatai Khanate suffered a similar fate.

Despite these setbacks, the direction had already been set. By the 15th century, the areas formerly governed by three of the four Mongol khanates—the Ilkhanate, Golden Horde, and the Chagatai—had largely embraced Islam. The legacy they left behind would set the stage for Islamic civilisation’s historical apex.

Islam’s Apex: The Balkan-to-Bengal Gunpowder Empires

Islamic history did not come to an end in 1258, or any time thereafter. After the disintegration of the Mongol empire, the Chinggisid successor states such as the Ilkhanids, Timurids, and Mughals proved Islamic civilisation’s dynamic capacity to absorb and redirect once-hostile forces into a new, vitalistic source of energy. Even non-Chinggisid states would be influenced by the Turco-Mongolian synthesis.

By the 16th century, Islamic civilisation was reconstituted under some of the largest and most centralised polities in Muslim history: the gunpowder empires. These new states, the Ottomans, Safavids, and Mughals, were not only militarily impressive, culturally sophisticated, and materially wealthy, but reshaped Islamic governance and society on a vast scale, leading arguably to the first truly universal Islamic civilisation from West Africa to the Philippines.

The Timurid dynasty, founded by Timur in the early 14th century was the direct product of the Turco-Mongol ethnocultural synthesis, and it was he and his descendants who carried this legacy to neighbouring regions and to the Indian Subcontinent. Timur himself sought to legitimise his rule by marrying into the Chinggisid royal family and, in the words of Peter Jackson, “combined Islamic zeal with a strong attachment to Mongol traditions, including the Yasa.” The Timurids, who ruled over Transoxiana, Khorasan, Afghanistan, Iran, and parts of Central Asia, adopted many Mongol administrative practices, including the Yasa, tax systems, and military organisation.

In India, the Mughal Empire—at its peak the wealthiest and most populous Islamic polity there had ever been—took its name from the Mongols. The first Mughal Emperor, Babur, presented himself as an heir to both the Chingissids and the Timurids, destined to rule and expand his realms. Like the Ottomans, the Mughals shared a common political culture that drew heavily on both Central Asian and Persian traditions.

In Anatolia, numerous waves of Turkish refugees fled Mongol invasions, putting pressure on the Islamic frontier with Byzantium. These invasions also smashed the aged structures of the Seljuk empire, resulting in the creation of numerous beyliks. One of these small beyliks, nestled in northwestern Anatolia, would be led by Osman I, the eponymous founder of the Ottoman empire. Between the 14th century and 16th century, the Ottoman dynasty and their vassals expanded their rule over the Balkans, Middle East, and North Africa.

These empires were radically different from earlier Muslim polities. They took on many of the attributes of what we today see as the modern state: ‘constitutional’ theories on the relationship between the ruler’s legislative and executive powers, the introduction of the Ulema into the state apparatus, the formation of permanent, impersonal, and centralised bureaucracies, and the establishment of permanent, “gunpowder armies” utilising muskets and cannons. Much of this was driven by the natural need to govern such large expanses of territory, the utilisation of new technologies in transport and communications, but also innovation in Islamic theories of power of legitimacy that evolved after the Mongol conquests to become truly imperial in scale.

The new era also saw the emergence of a Turco-Persianate Islamic ‘high culture’ as Persian became the lingua franca of Turkic dynasties across the vast expanse that Shahab Ahmed termed the ‘Balkans-to-Bengal complex’, equivalent to the use of French in early modern Europe. The use of Persian as a lingua franca would not be superseded by any other language until English became the global lingua franca in the 19th century.

The new centres of gravity in Islamic civilisation would expand outwards, primarily centred on the Ottomans and their capital at Istanbul, and the Mughals and their capital at Delhi. Islamic civilisation’s reach went beyond their immediate political control, as their cultural and economic clout influenced and even dictated those of their neighbours.

The scale and power of the gunpowder empires dwarfed anything mustered by previous Muslim polities and brings into question the theory of a long decline after the 13th century. This theory has handicapped our ability to recognise our civilisation’s resilience, adaptability and dynamism. Islamic civilisation has never followed a single trajectory of rise and decline but has instead moved through cycles of renewal and transformation.

The decline that had taken root in the historical heartland of Islamic civilisation is anachronistically blamed on the Mongols, obscuring a deeper reality: Islamic civilisation had moved on. The old cities of Islam like Damascus and Baghdad had grown weary under the weight of their history.

Ultimately, the Mongols were part of a wider movement, not just of people, but of the centres of gravity of Islamic civilisation. For good and ill, the Mongols became an undeniable influence on our civilisation and left its mark through various Turco-Mongolian successor states and the creation of a Turco-Persianate high culture, which would come to define Islam’s apex.

Yana Zuray(eva) is a Buryat-Mongolian visual artist and 3D designer from Ulan-Ude, Russia. She writes at Waterfalls of Qaf and can be found on X as @yiihya. She lives between Toronto and London.

You can follow Kasurian on Substack Notes, Instagram, and Twitter/X for the latest updates.

Further reading:

Books:

The Mongols and the Islamic World: From Conquest to Conversion; The Mission of Friar William of Rubruck: His Journey to the Court of the Great Khan Möngke, 1253–1255 - Peter Jackson

The Mongol Storm: Making and Breaking Empires in the Medieval Near East - Nicholas Morton

Violence and Non-Violence in the Mongol Conquest of Baghdad - Michal Biran

Studies in Muslim Apocalyptic; Apocalyptic Incidents during the Mongol Invasions - David Cook

Nomads as Agents of Cultural Change: The Mongols and Their Eurasian Predecessors - Reuven Amitai and Michal Biran (Editors)

The Horde: How the Mongols Changed the World - Marie Favereau

An Afterlife for the Khan: Muslims, Buddhists, and Sacred Kingship in Mongol Iran and Eurasia - Jonathan Z. Brack

The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353 - Linda Komaroff, Stefano Carboni

Central Asian Aspects of Pre-modern Iranian History (14th to 19th Century) - Bert Fragner

Mongols in Mamluk Eyes: Representing Ethnic Others in the Medieval Middle East - J.M.C. van den Bent

A Study of History - Arnold Toynbee

A History of Warfare - John Keegan

What Is Islam? The Importance of Being Islamic - Shahab Ahmed

Essays:

Long Live Mongol Iranzamin - Munkhnaran Bayarlkhagva

Did the Mongols Really Destroy the Books of Baghdad (1258)? Examining the Tigris “River of Ink” - Yusuf Chaudhary

Chingiz Khān: Maker of the Islamic World - George Lane

Beautifully written! A truly unfortunate state that Muslims find themselves in today is one which has almost intentionally decapitated itself from its historical lineage. Perhaps as a result of the colonization of both our cities and minds, we’ve relegated our entire positive history to the Umayyad and Abbasaid empires and ascribed everything following it up to the 19th century as a regressive stain, serving as the principle cause of our intellectual and military stagnation which therefore needs be forgotten of. In a form of collective apathy, we’ve become foreign to our own selves.

amazing!!