Kasurian: A Magazine for the 21st Century

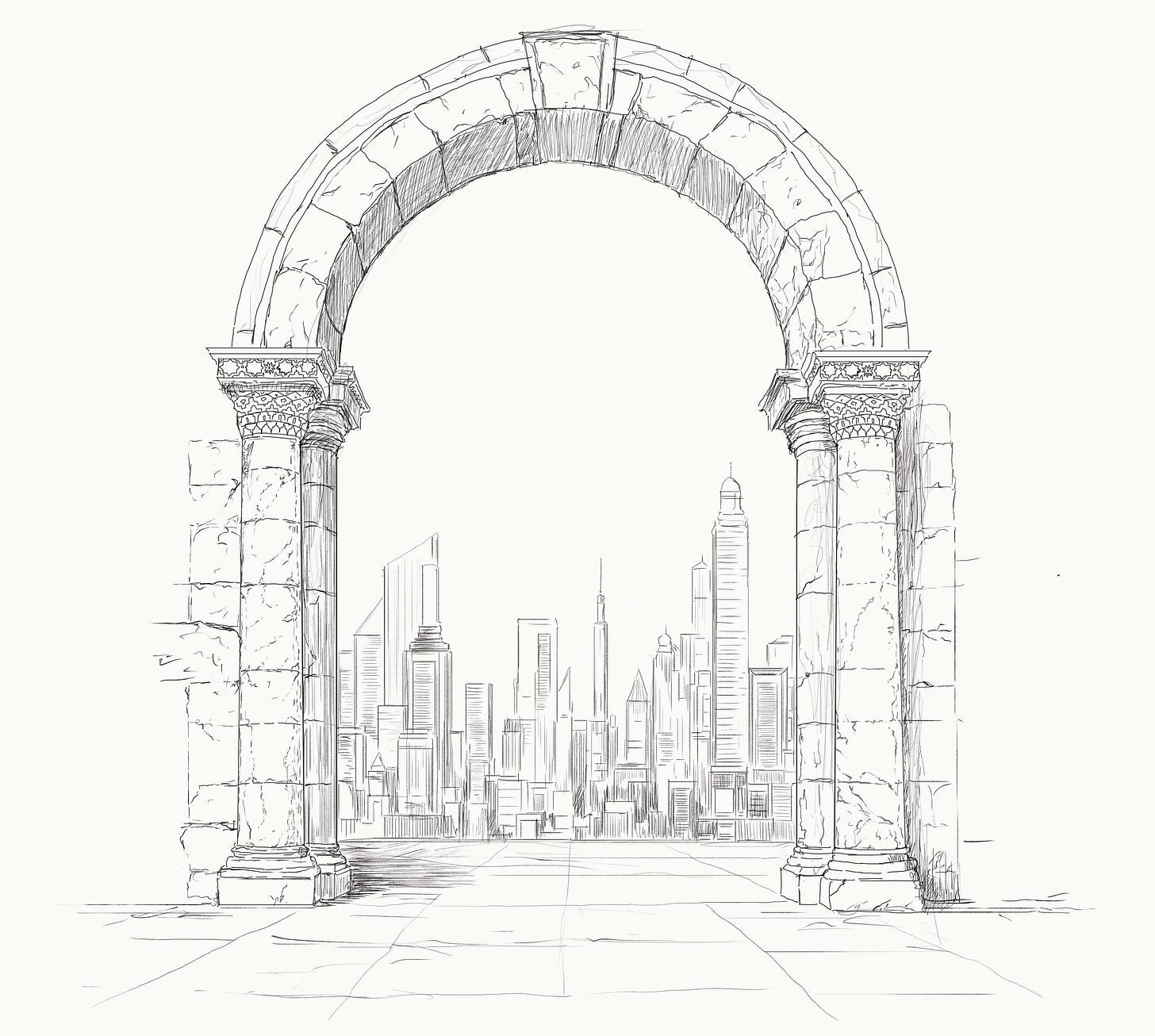

Why does Kasurian exist, and what can you expect from us?

The ‘Short 19th Century’

Where do ideas come from? A broad sweep of history creates the illusion of a smooth landscape where every period is equally and progressively generative in knowledge and culture. On closer inspection, however, that landscape transforms into a rugged panorama of great peaks and low valleys. In different times, places, and material conditions, short periods of creativity burst forth–and leave as quickly as they come.

In The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Thomas S. Kuhn introduced a new theory to conceptualise the production of scientific knowledge, not as a linear, accumulating process, but as cycles of production, consumption, and decline punctuated by paradigm shifts that ignite new cycles of creative production. Kuhn’s theory extends to all forms of knowledge. Revolutionary periods of creative production such as 4th-century BC Athens, 9th-Century AD Baghdad, and 16th-century Renaissance Italy are unique moments not just in the cultural trajectory of their respective civilisations, but across human civilisation as a whole. They are the peaks from which most of humanity’s accumulated knowledge flows.

Why does this matter? The origins of the contemporary Muslim intellectual tradition lie in the short 19th century, when a culture of letters emerged to renegotiate Islam’s position in the modern age. This period of history is poorly understood today but it is crucial in uncovering the origins of our ideas and assumptions about the ‘modern world’. The short 19th century’s abrupt and violent end also helps explain why Muslims have since struggled to build a cultural and intellectual tradition of equal, let alone greater significance. If our quest is to incubate a generative culture for our time, we can only do that by understanding our history – not as mere mythology or a recollection of facts, but by developing a real theory of history with explanatory power that rationalises patterns and events.

Today, the Muslim world fares poorly when it comes to cultural and intellectual production, falling closer to the bottom of global charts in metrics like book printing, intellectual property and patents, scientific research, and general cultural status. Generation after generation, the same issues are debated in the same language–although increasingly worse for wear–without resolution. All the while, there is a denial that Islamdom was ever in crisis and that it is modernity itself was an evil aberration, like oil to the water of Islam. Others insist that the Islamic world’s intellectual stagnation persisted throughout the modern era, incapable of rising up to the challenge.

In truth, the Muslim mind suffers from amnesia towards a crucial chapter in our recent history. Napoleon Bonaparte’s entry into Egypt at the turn of the 19th century was one of Islam’s first major interactions with industrialising Europe. The force and fury with which European arms and science came laid bare the weakness of Islamdom. In one sense, the 19th century was indeed a period of stagnation, the tail-end of an exhausted civilisation. But it was also a period of reimagining: this rude awakening saw Muslims re-appraise Islam’s relationship with law, culture, new political structures and forms of legitimacy, and scientific knowledge; all these and more became part of a negotiation that reasoned from Islam’s first principles to recreate Islam’s feudal plausibility structure for an industrial age.

The key medium for this renegotiation was the written word. The opening salvo of the movement was the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II’s launch of the first Turkish-language gazette, Takvim-i Vekayi, in 1831. By the 1870s, this movement was in full swing. Muslim thinkers took to modern communications and cultural mediums with gusto. Networks of writers could communicate thanks to the telegraph, the printing press allowed the mass distribution of new ideas among the masses and promoted wider literacy, and the ecosystem of knowledge in Islamdom began to expand.

Cities across the Islamic world through Cairo, Kazan, Istanbul, Damascus, and Lucknow became centres of an unprecedented transnational network where printing presses were set up, magazines were founded, and a rich world of print publications emerged. Islamdom had never been so connected, its intellectual reach so far. Muslim publications were even founded by politicians and thinkers in exile in several European cities, including London, Paris, and Vienna. In the Arab world, Damascus, Beirut, Alexandria, and Cairo incubated the Nahda (“Renaissance”), a period of Arab cultural revival facilitated by a novel newspaper ecosystem. The Jadidi movement spread reformist ideas through dozens of Tatar-language journals to Muslim communities across the Russian empire, primarily aiming to reform education to reconcile the traditional Islamic curriculum with modern European knowledge.

The ideas and narratives that shaped Muslim responses to European concepts like nationalism, secularism, democracy, and the nation-state were formed in the short 19th century’s era of internal debate. The Ottoman journal Sebilürreşad, founded in 1908 (then closed in 1966, and recently reopened in 2016) by the famous national poet Mehmet Akif Ersoy, would incubate the foundational principles of ‘Islamist thought’ that still predominate today. Among Sebilürreşad’s most frequent contributors was the Ottoman statesman and vizier (1913-1917) Said Halim Pasha, whose works İslâmlaşmak and Meşrutiyet seem like they could have been written today, not at the turn of the 20th century.

Islamdom in the 19th century did not stagnate and collapse in the face of Europe’s sudden arrival at its gates. Instead, it mounted a lively rear-guard response, giving rise to a new paradigm of knowledge and culture that still underpins much of our intellectual framework today.

The End of the Short 19th Century and its Aftermath

WWI was an abrupt and violent end to Islamic civilisation’s modern revival. Elite networks of power and patronage were dismembered, depriving Islamdom of its high culture and crucial support base for the production of knowledge. Colonial compradors and secular nationalists from Albania to Turkestan hunted down the Muslim intelligentsia, imprisoning, silencing, or killing them in vast swathes. The ulema and their guardianship of the sharia were put under siege as European-style secularism was imported to replace what was previously an Islamic ecosystem of worldly knowledge. The networks, traditions, and bodies of knowledge that formed the bedrock of Islamic civilisation were severed, and efforts to negotiate Islamdom’s transition into the industrial age put to an end.

A few decades after WWI, the Algerian sociologist Malik Bennabi waded amid the ruins of Islamic civilisation and concluded that Muslims had simply stopped producing new knowledge. Bennabi diagnosed this ailment in the Muslim mind as colonisabilité, the Muslim’s defeated state under colonisation in which intelligence did not necessarily translate into creativity and innovation.

Decades after Bennabi’s insights, little has changed: we have had successive generations of Muslim thinkers and intellectuals who are nearly entirely handicapped in their ability to produce new ideas. If one carefully traces the lineage of ideas in 2025 among both the Muslim intelligentsia and laymen, one finds that these are progressively degenerating ideas borrowed from each previous generation back to when they were first produced in the short 19th century. If Bennabi were alive today, he would despair at the Muslim world’s state of affairs, and that the ideas that had been circulating in his time are the same ideas circulating today–only in a worse form.

Since the end of the short 19th century, the absence of a true culture of letters has deepened this crisis. Without flagship publications to articulate the issues and concerns of our time and allow writers to present ideas, Muslims lack one of the necessary infrastructures to generate and refine new ideas. In lacking a true understanding of Islamic history, we remain unaware of the wider paradigm of knowledge and culture under which we operate. As a result, any assessment we make in finding solutions for our current predicaments is likely to be wrong. Ultimately, this ensures we can never reach the future.

The short 19th century’s most important lesson is that even in Islamic civilisation’s darkest moments, we still possessed the vitality to build a culture of letters. We also learn that many of our ideas today stem from that period because we lack a healthy, indigenous culture of letters of our own. It is difficult to find Muslim publications or writers of note outside of the narrow confines of academia, writing for general audiences on a wide variety of topics and arguing in well-reasoned prose–necessary requisites for new ideas to blossom and spread. Instead, the sense-making institutions we rely on are produced by others. The New Yorker, the Financial Times, the New York and London Review of Books, n+1, the Wall Street Journal, the Washington Post – we have no similar flagship publications dedicated to our worldview, our values as they relate to the pillars of civilisation - including politics, economics, history, architecture, literature, science, technology and art. A generative culture cannot exist without a lively commons which is shaped by similar such “indigenous” sense-making institutions.

What is Kasurian?

Kasurian exists, in part, to fill some of the gap left by the abrupt end of the short 19th century, where a culture of letters thrived and died, and its place in the wider course of history has been forgotten.

Today, there is no ‘commons’ for discourse and is at least one of the reasons why our capacity to produce new ideas has become limited. We hope that Kasurian acts as a modest contribution towards rebuilding a culture of letters that may one day grow or catalyse a paradigm of culture and knowledge. Achieving this requires more than one individual, group, or publication alone: we all have a part to play in the production of knowledge that contributes to a new understanding of Islam in the 21st century.

Curiosity and conviction is our tagline. Kasurian is for those who seek to understand the world and aspire to have more agency in it. Some struggle to reconcile Islam with the material realities of modern life. Our goal is to create that bridge by inviting thinkers and practitioners from diverse fields to share their expertise, articulate ideas, observations, knowledge and engage in meaningful discourse.

Part of Kasurian’s mission is to rediscover Islamic history. The 19th and 20th centuries are relevant as a period in which Muslims established a vanguard of intellectual and cultural production to deal with the new world and negotiate our place in it–and lost it all. Revisiting this moment allows us to trace the tradition of ideas that persist in the present, place them in their proper context, and recognise that the present moment needs novel ideas and a vocabulary better suited for the 21st century.

Engaging earnestly with the present is essential. The rejection of the status quo in favour of a nostalgic historical imaginary has done us no favours. Instead of engaging with the material reality we are embedded in, our rejection of it has made us ignorant of the wider forces at play in the world.

Our first issue sets the stage for future issues: a collection of essays on history, culture, institutions, and technology. We set the stage by emphasising the agentic nature of the production of knowledge and culture through The Lost Art of Research as Leisure: today, we have more freedom than ever before to participate in what was previously the preserve of the aristocratic class. From there, we turn to history, exploring the resilience of Islamic civilisation in the face of an existential threat. We examine how Muslims responded to the Mongol invasions by integrating them into our civilisation, eventually elevating Islamdom to new heights throughout the Balkans-to-Bengal complex of the gunpowder age.

Moving into the modern era, we uncover the forgotten history of the twentieth-century union between the House of Osman and Hyderabad, and their last-ditch effort to preserve the Ottoman Caliphate in the heart of India. Alongside Islam’s aristocratic class, the loss of its early modern ‘bourgeoisie’ at the forefront of the short 19th century’s cultural and intellectual efforts was most dramatic and total in their destruction in post-Ottoman Albania.

Beyond Islamdom, we examine how cultural production is shaped and engineered through institutions, using Britain’s Royal Society of Arts as a case study and offering a different perspective on how culture emerges. Aligned with our belief that brilliance can exist in times of stagnation, we look at the Lebanese Space Program in the 1960s and the lessons we can learn on bootstrapping complex technological projects under precipitous conditions.

We hope that this issue – and all future issues – piques your curiosity, and serves as a small and humble step towards reviving and eventually surpassing the conversations that once flourished in the short 19th century. Our aim is that Kasurian leaves you conscious of the past, curious about the present, and confident in the future.

You can follow Kasurian on Substack Notes, Instagram, and Twitter/X for the latest updates.

Further Reading:

Late Ottoman Origins of Modern Islamic Thought - Andrew Hammond

The Crisis of Islamic Civilisation - Ali A. Allawi

The Islamic Secular – Sherman A. Jackson

The Question of Culture - Malik Bennabi

The Square & The Tower - Niall Ferguson

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions - Thomas S Kuhn

I found https://kasurian.com/p/research-as-leisure via aldaily.com. I am a Christian, ignorant of Muslim intellectualism. I shall ponder your work here, and I shall ponder how to engage with it beyond this trivial comment.

"More critically, in lacking a true understanding of Islamic history, we remain unaware of the wider paradigm of knowledge and culture under which we operate. As a result, any assessment we make in finding solutions for our current predicaments is likely to be wrong. Ultimately, this ensures we can never reach the future."

~ Beautiful articulation of the colonised mindset many of us Muslims in the West are struggling with.

May your publication be means of diversing our views of modern times from purely a western lens (i.e. individualistic, capitalist, materialist, secularist) to a more Islamic one, grounded in reverence, balance, humbleness and gratitude.