In Abraham's Shadow

On humanity's axial turn away from human sacrifice, and why Muslims celebrate it every year.

In those ancient times, in those ancient days.

So opens the Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the oldest recorded works of literature, chiselled in clay tablets for eternal memory some 4,000 years ago. Ancient enough to us today, these opening lines contemplate the vast expanse of time that has passed between those ancient days, the Bronze Age city-states of the Fertile Crescent in which the Epic was first recorded, and our own time today. The burden of uncertainty we shoulder towards our past today was no less weighty to those we consider the ancients, who saw themselves as youth in the shadow of an even greater past.

The Qur’an calls for tadabbur, a deep contemplation, over the ruins of once mighty civilisations laid to waste by time and human folly.

Is it not yet clear to them how many peoples We destroyed before them, whose ruins they still pass by?1 We are asked.

Surely in this are signs for people of sound judgment. We are challenged.

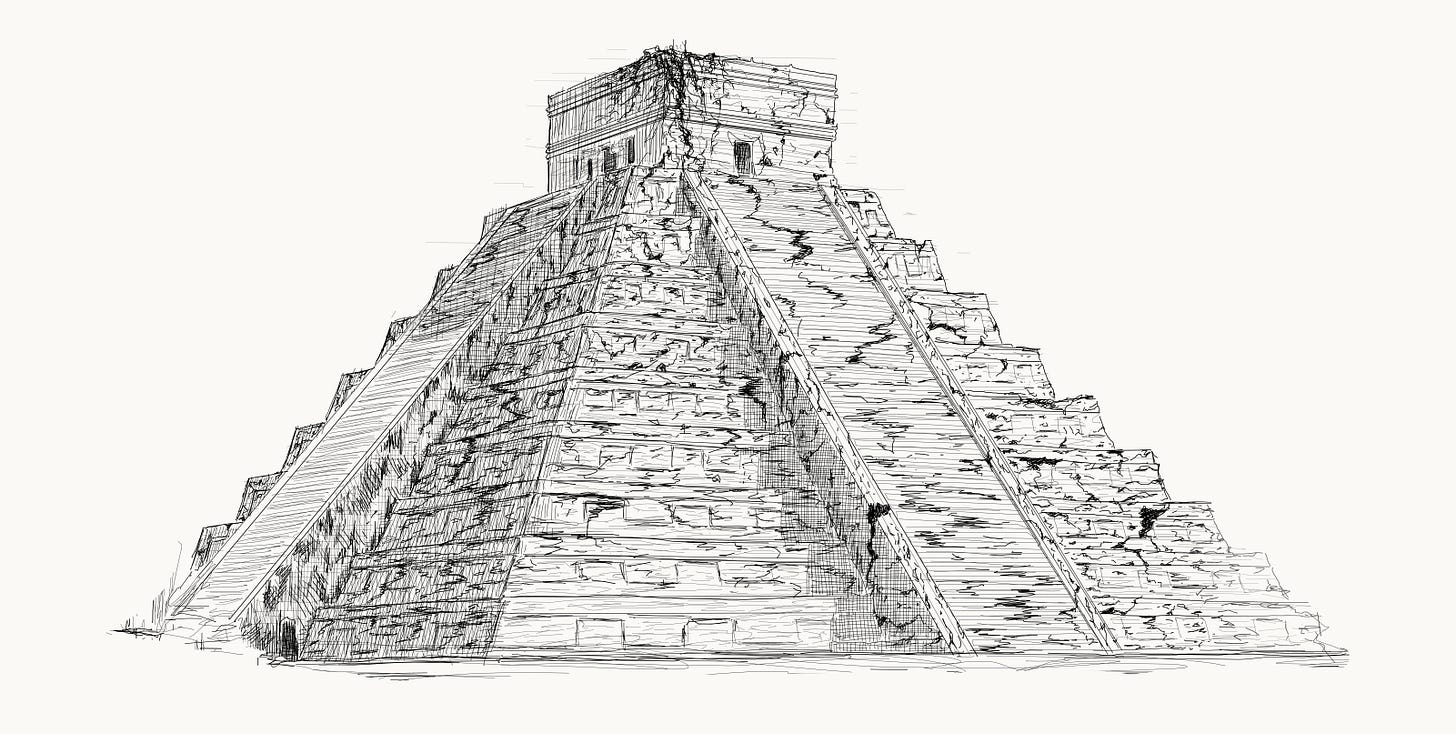

To gaze upon the ruins of dead civilisations and contemplate their mortality reveals the perennial condition of man and history.

Contemplation of destroyed civilisations is constrained by the scarcity of evidence. The plains of Mesopotamia have changed. The great fathers of agricultural civilisation, who were nourished by its produce, warred over it, and built great kingdoms and empires, have lain in long silent slumber for millennia beneath the undulating Tells that give shape to the Mesopotamian plains. Their palaces and walls have largely turned to dust. The rivers have adjusted their course. The land is less fertile, rain is sparse, and the summers are severe. The land croaks under the accumulated burden of civilisation that has turned soil to sand.

Yet, if you stood there for a moment, you might almost see past the thin membrane that separates material reality from time, and you can imagine what the ancient civilisations that used to dwell here may have looked like. The long shadows cast on the landscape by these Tells come alive with the ghosts of the past, conversing in a vernacular not entirely alien to the inhabitants of this land today. Those Tells turn into fortresses and grand mausoleums, roads emerge from the wild landscape teeming with messengers, traders, and armies, and a dry countryside turns into busy harvests. Why did this disappear? And why have all civilisations succumbed to ruin?

The doom of Mesopotamia is the doom of all nations at one point or another. Yet, those great Bronze Age city-states of 4,000 years past were not the first to succumb to extinction. Near the Mesopotamian city of Urfa, now in modern-day Turkiye, archaeologists plumb the depths of deep time to reveal an age undreamed of, even to those who lived in those ancient days. The discovery of Göbekli Tepe, an archaeological site excavated for the first time in 1994, challenges the orthodox account of man’s historical transition from roaming to sedentary civilisation.

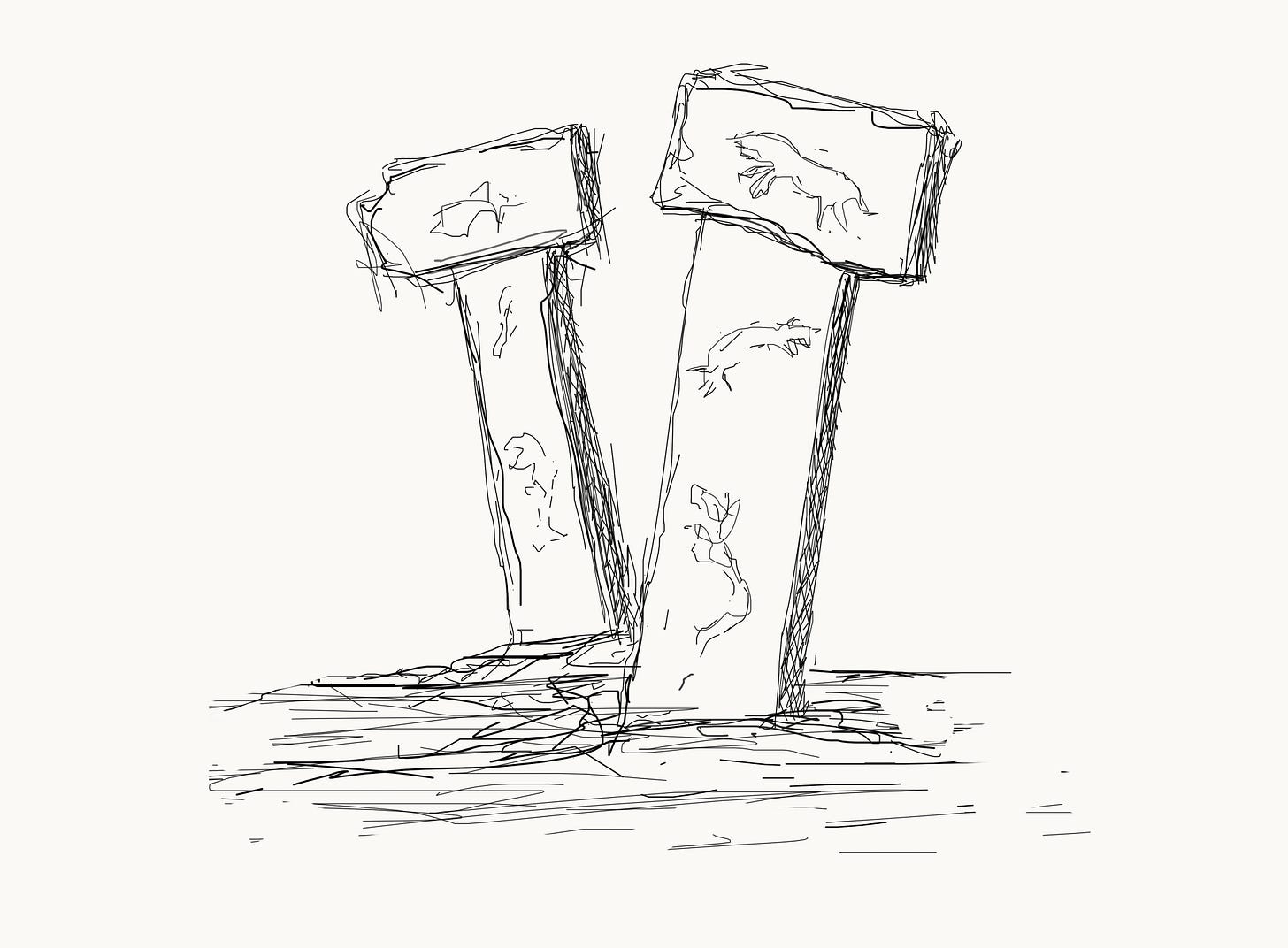

Built around 12,000 years ago, Göbekli Tepe’s discovery compels a re-imagination of humanity’s deep history and the origins of agricultural civilisation. Great T-shaped obelisks decorated with a pantheon of zoomorphic imagery: foxes and lions, vultures and scorpions, geese and wild boar; some of these animals have never been native to the region or have been driven to extinction by humanity over the millennia. According to this account, a settlement of the size, location, and era of Göbekli Tepe should not exist. Yet, exist it does. Questions abound. Were the obelisks worshipped? Were they recordings celebrating the land's rich agriculture and wildlife? Could they, as some have theorised, have sought to depict the animals of Noah’s Ark? Who were its builders? What gods did they worship? And what was the purpose of this grand temple that has now re-emerged from the plains? Perhaps we will receive answers to some of these questions as archaeological excavations reveal more. All we know is that in a time almost equidistant between ourselves, the ancient Egyptians, and the world of Göbekli Tepe, thousands of years of what was most likely a sedentary, agricultural civilisation persisted beyond the horizon of recorded time.

And yet what we discover of Göbekli Tepe’s religion and rituals may not be so alien to us. Contemplating deep history reveals the vicissitudes of humanity’s moral assumptions. All is not set in stone, and the pagan attitudes that predominated in humanity’s deep history may yet make a vengeful return.

To understand these processes requires a reckoning with what is being lost from our moral fabric today, and to do that, we must understand its origins.

The prophet's return is creative. He returns to insert himself into the sweep of time with a view to control the forces of history, and thereby to create a fresh world of ideals. For the mystic the repose of "unitary experience" is something final; for the prophet it is the awakening, within him, of world-shaking psychological forces, calculated to completely transform the human world. The desire to see his religious experience transformed into a living world-force is supreme in the prophet. Thus his return amounts to a kind of pragmatic test of the value of his religious experience.

– The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam, Muhammad Iqbal

In the centuries when the Epic of Gilgamesh is chiselled into clay, in which Ea-Nasir hawks his poor-quality copper to irate clients, a world of bronze swords and chariots, where God-Kings reign with supreme confidence in their immortality even as their doom nears; in the Fertile Crescent, a prophet embarks on a greater odyssey that will result in the axial transformation of humanity’s basic moral precepts.

In ancient Ur, Abraham stands alone among his people in opposition to the worship of man-made idols. He gazes on the heavens in deep contemplation to discern the true nature of God.2 As night gives way to day, and day gives way to night, Abraham looks to the stars, moon, and sun for signs of divinity. He finds none. Abraham’s contemplation discerns the mortality and ruin of pagan idols. A true God cannot die. Thus in Abraham awakens those ‘world-shaking psychological forces’ to ‘create a fresh world of ideals’ and create an axial shift in humanity’s moral condition. He takes a hammer to the idols his people worship, and when interrogated as to discover who destroyed them, Abraham replies, “Ask them, if they can speak”.3

Facing persecution for his opposition to idolatry, Abraham’s odyssey begins, travelling the breadth and width of what is today the Middle East to find a home in which his call to true monotheism could flourish. It is deep in Arabia, in the vicinity of Makka, at the heart of which Abraham settles and builds the ‘black stone’ known as the Ka’aba, where God speaks to him again.

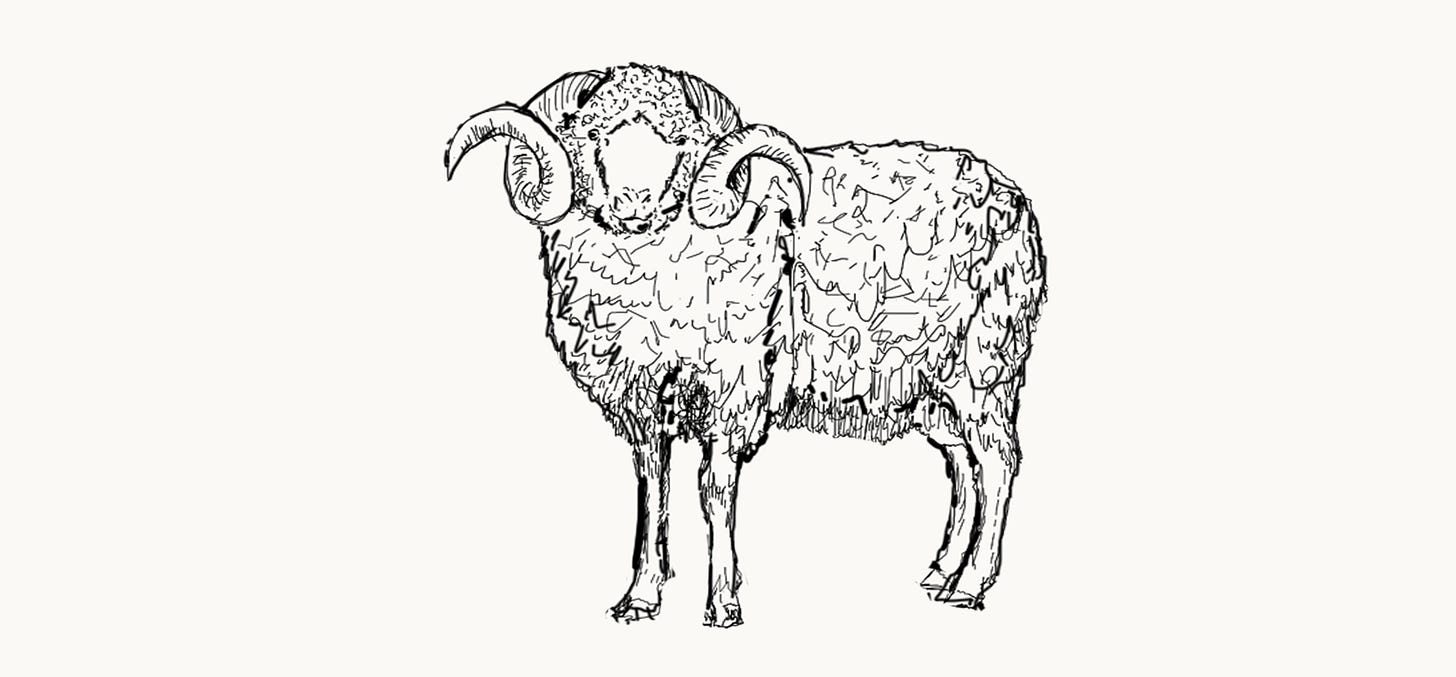

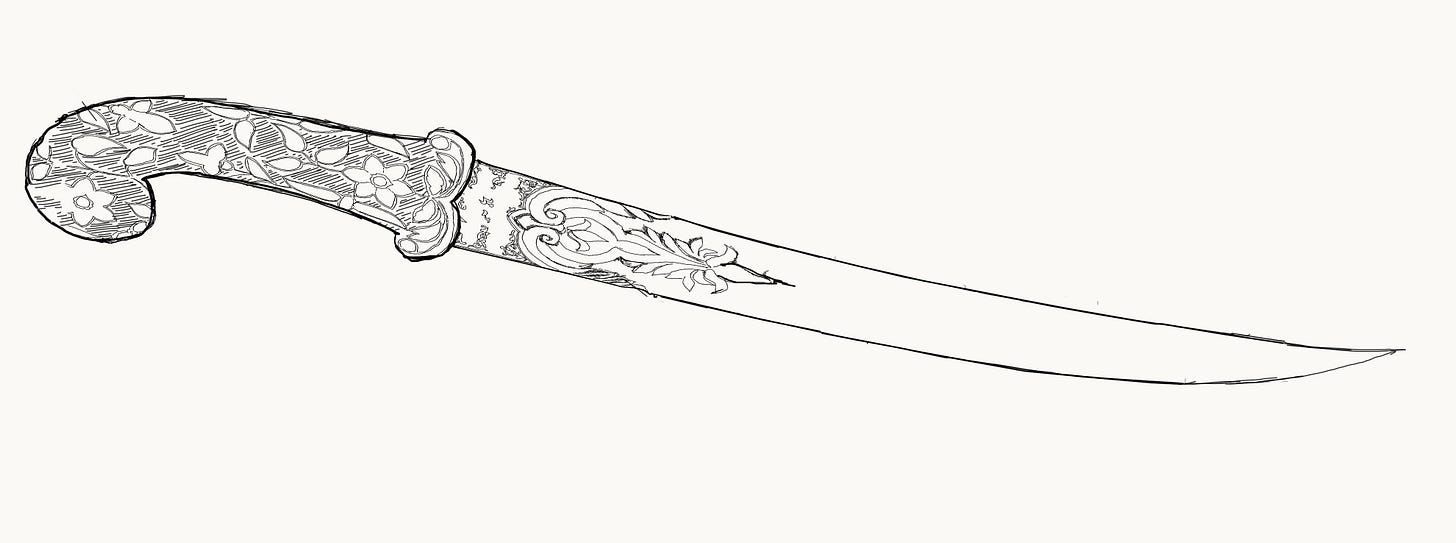

God commands Abraham to sacrifice his son, Ishmael, to prove his faith. In true faith and submission, both Abraham and Ishmael comply with this command. As the knife descends, God prevents Abraham from sacrificing Ishmael and declares that ‘this sacrifice would henceforth be replaced by ‘a greater sacrifice’, and replaces Ishmael with a ram to be sacrificed in his stead.

For over 1400 years, Muslims have commemorated this event and Abraham’s pilgrimage by performing the Hajj pilgrimage to Makka and circumambulating the Ka’aba. The Hajj concludes with the annual Feast of the Sacrifice (Eid al-Adha), a celebration of God’s mercy towards Abraham, during which Muslims sacrifice animals and distribute their meat to the poor.

The Feast is more than ritual gratitude for Abraham’s faith and God’s mercy. It is the remembrance of a world-historical shift in humanity’s moral dimension, with Abraham as the divinely ordained harbinger whose laws, until today, inform our most fundamental beliefs in right and wrong, our attitudes on the sanctity of life, when and when not to kill, what is sacred and profane, and where man’s capacity to reason his way to moral action ends. In fact, Abraham’s message has been so successful that an increasingly irreligious world has largely forgotten that their source of morality is in large part owed to him.

It is humanity’s tendency to forget that leads to many questions today as to how Abraham could countenance the sacrifice of his own son. Abraham was raised in a world in which ritual human sacrifice was the norm, and God’s call to sacrifice his son would not have appeared as immoral or fraudulent. God’s mercy was not just to save Abraham from the consequences of sacrificing his own son, but also to forever replace the ritual slaughter of men with animals. Contra Kierkegaard’s anxieties, Abraham’s sacrifice was not a teleological suspension of the ethical, but a contextually reasonable and ethical willingness on the part of Abraham to do what humanity had always done, except in service of a true God, not a false idol.

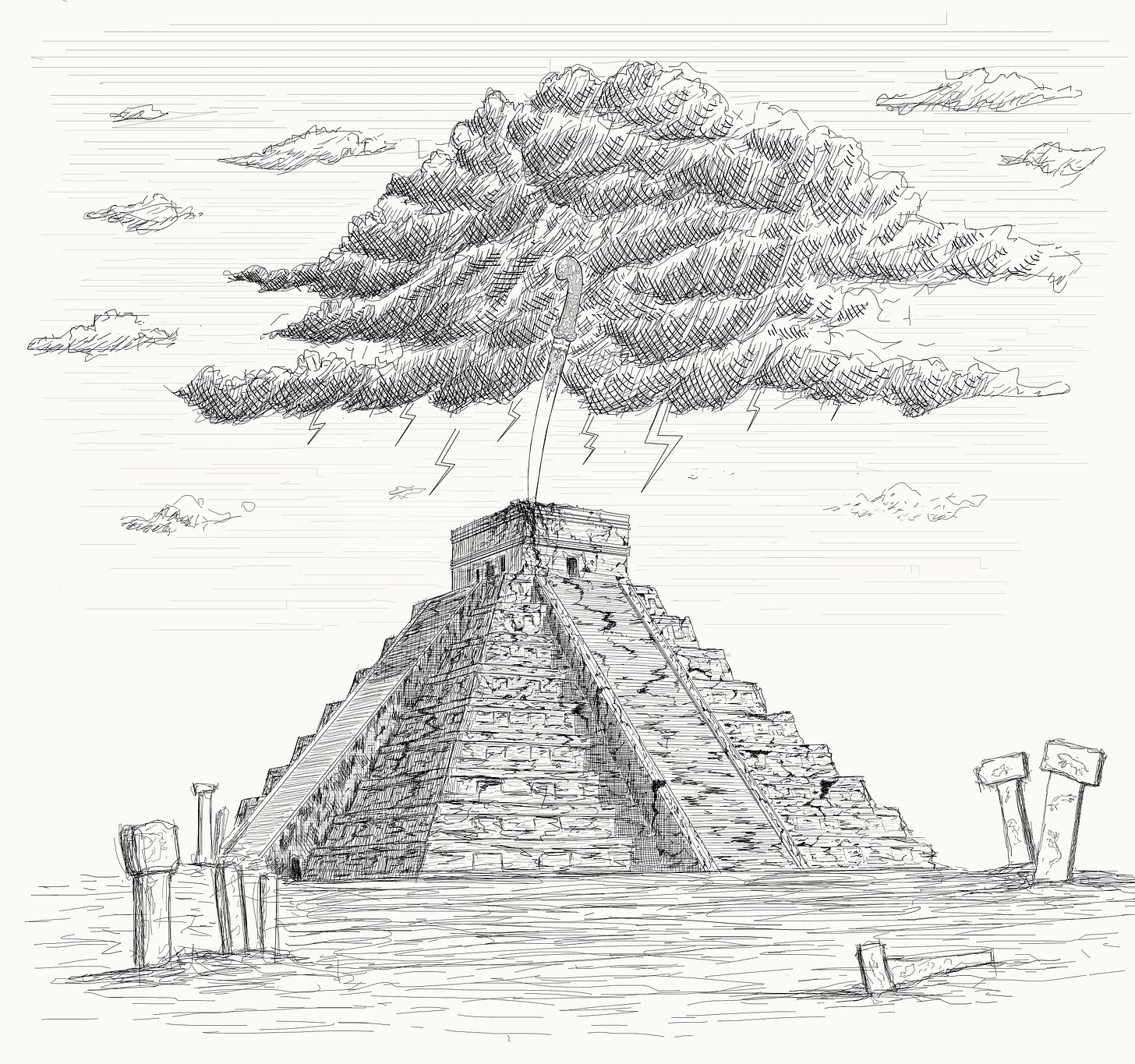

Our revulsion towards human sacrifice is a recent phenomenon in the grand scale of history: In the Andes, children were left to freeze alive; The Aztec’s founding myth was the skinning of a princess whose skin was worn as a cloak by the Aztec priest whose tribe would go on to form the Aztec empires, and its great pyramids dedicated to the sacrifice of tens of thousands of souls; In India, Sati, or bride burning; In Ancient Egypt and the Shang dynasty in China, the burying of servants alive their rulers; In Carthage, the infant sacrifices. Human sacrifice was a global phenomenon, and particularly widespread in pagan and highly stratified societies.

Bereft of divine revelation and left to our own devices, humanity has often assumed that the greatest offering to their Gods was the life of other men. It is something that contemporary man can barely begin to fathom, assuming that our moral attitudes against the practice emerged almost by happenstance, or that some philosopher had reasoned his way to the fact that human sacrifice was wrong. By some process or another, over time, entire cultures and civilisations bought into the idea, and eventually, the practice became nearly extinguished around the world.

None of this was an emergent phenomenon. The abolition of human sacrifice has been driven by the singularly successful message carried forward throughout the Abrahamic Odyssey, which has sustained itself across generations and millennia, buoyed by the singular command of the Lord of Hosts: go forth and multiply. Abraham is thus called the Patriarch, considered in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, as a founding father in the lineage of Adam and Noah. In Islam, Abraham holds a special status as the ‘friend of God’, and a Hanif–a true monotheist. The sheer dominance of the moral frameworks that have emerged out of these religions lives on today in a world whose basic moral precepts have been shaped by Abraham. And one of the Abrahamic faiths’ fundamental contributions to humanity has been the abolition of human sacrifice wherever they went.

The preponderance of human sacrifice in pagan societies may be explained by the philosopher René Girard’s theory of ‘mimetic desire’, in which ‘archaic’ societies ritually controlled violence driven by envious desire through the ‘transfer’ of guilt to a sacrificial scapegoat, who would be collectively attacked by society as a means of restoring the balance. These societies masked collective guilt with myths of divine necessity, which meant that more often than not, human sacrifice would occur as a ritualistic offering to their Gods.

In Islam, Abraham’s sacrifice is a turning point in which guilt, once associated with human sacrifice, is symbolically transferred to an animal, whose sacrifice represents less the fear of divine wrath and more devotion to a merciful God. It is a call to ethical accountability, in which mindless social violence that arbitrarily chooses victims to excise itself of this violence and restore order is replaced by forgiveness.

The morality of the non-religious man has its source in religion, but in an earlier, forgotten religion...The sun has set, but the warmth that radiates in the night comes from the sun.

– Alija Izetbegović

For those who ponder, the Feast is a memory of a time before, when men had no qualms about the practice of human sacrifice. Such was its ubiquity that Abraham himself committed to the sacrifice of his son as an act of devotion to God, whose divine intervention finally transformed our moral attitude towards the practice of human sacrifice.

Gazing at the ruins of civilisations and their fallen moral orders and religions, one feels a sense of unease looking ahead. We may feel the dimming warmth of faith at our backs, but ahead of us yawns a cold, stygian silence. For its part, the decline of religion in the West has led to a great deal of moral uncertainty and anxiety. The loss of shared rituals, norms, beliefs, and morals is creating ever more distrustful and insular societies. Strange permutations in culture, considered verboten in today’s moral code, herald new norms the next day. Lacking a moral anchor, civilisation increasingly feels like an arena of predators, devoid of mercy and devoted solely to a will to power. Society’s vindictiveness, the collapse in the rule of law, and the increasing intensity of tribal desire to exact vengeance on others echo a return to the mimetic desires that once led men to sacrifice each other. We no longer have the confidence that our inherited morality, fostered in a religious framework, can hold the line against horrors beyond our comprehension.

History offers little solace. The cycle of glory and ruin that characterises all civilisations suggests an inescapable doom. Were Göbekli Tepe’s altars also bloodied with human sacrifice? Is the morality of the people who once lived, sacrificed, and died there so different from the morality emerging in our time? Or, as T.S. Eliot lamented, have the cycles of heaven brought us farther from God and nearer to dust, like a great moral ourobouros? Perhaps when the dust settles on excavations at Göbekli Tepe, what we assume will be a strange and terrible world revealed to us would instead appear hauntingly familiar.

In these times, Eid al-Adha carries a new significance, an annual renewal of a vow against the re-emergence of human sacrifice, and to the path of Abraham the Hanif. What seems new is very old, and in such times, the accusation that religion is a ‘thing of the past’ may be to its credit; for when men have forgotten their past, religion’s traditions remain deeply embedded with its lessons and consequences. Chief among them, that all that stands between the sanctity of human life and the return of human sacrifice is the knife of Abraham.

Ahmed Askary is Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Kasurian, a magazine focused on history, culture, and civilisation, and Vizier, a journal for political economy in the MENA region. You can follow him on Twitter/X at @pashadelics.

All art has been custom-drawn for Kasurian by Ahmet Faruk Yilmaz. You can find him on Instagram and Twitter/X at @afaruk_yilmaz.

Follow Kasurian on social media via Substack Notes, Instagram, and Twitter/X, for the latest updates.

Ta-Ha: verse 128

Al-An’am (The Cattle): verses 76-79

Al-Anbiya (The Prophets): verse 63

This is great and new perspective. Beautifully written, God bless you brother!

Allahuma Barik!

Relevant and related ideas threaded together beautifully into sage advice and a stark warning; the quranic instruction of pondering the past, the gift of abrahamic morality, and the story behind eidul-adha. As people take their inherited morality for granted they risk losing it, and with that risk the return to more ancient forms of morality. And so the importance of looking back into our past, and honouring and understanding rituals like eidul-adha, cannot be understated.