The Conspiracy to Save the Ottoman Caliphate in India

How the union of two great dynasties (nearly) changed world history.

“India is the greatest Muslim country in the world,” proclaimed the philosopher Sir Muhammad Iqbal in 1930. “India is perhaps the only country in the world,” he argued, “where Islam as a society is almost entirely due to the working of Islam as a culture inspired by a specific ethical ideal.” Indian Muslims, the world’s largest Muslim population, had no shared ethnicity or language. It was Islam alone which made them a community. “We have a duty towards Asia, especially Muslim Asia,” Iqbal maintained, since “70 millions of Muslims in a single country constitute a far more valuable asset to Islam than all the countries of Muslim Asia put together.”

We have lost a crucial part of Islam’s recent history. Almost entirely forgotten today, India - by which I mean the subcontinent, not the modern nation-state - was in many ways the epicentre of the Islamic world in the early twentieth century.

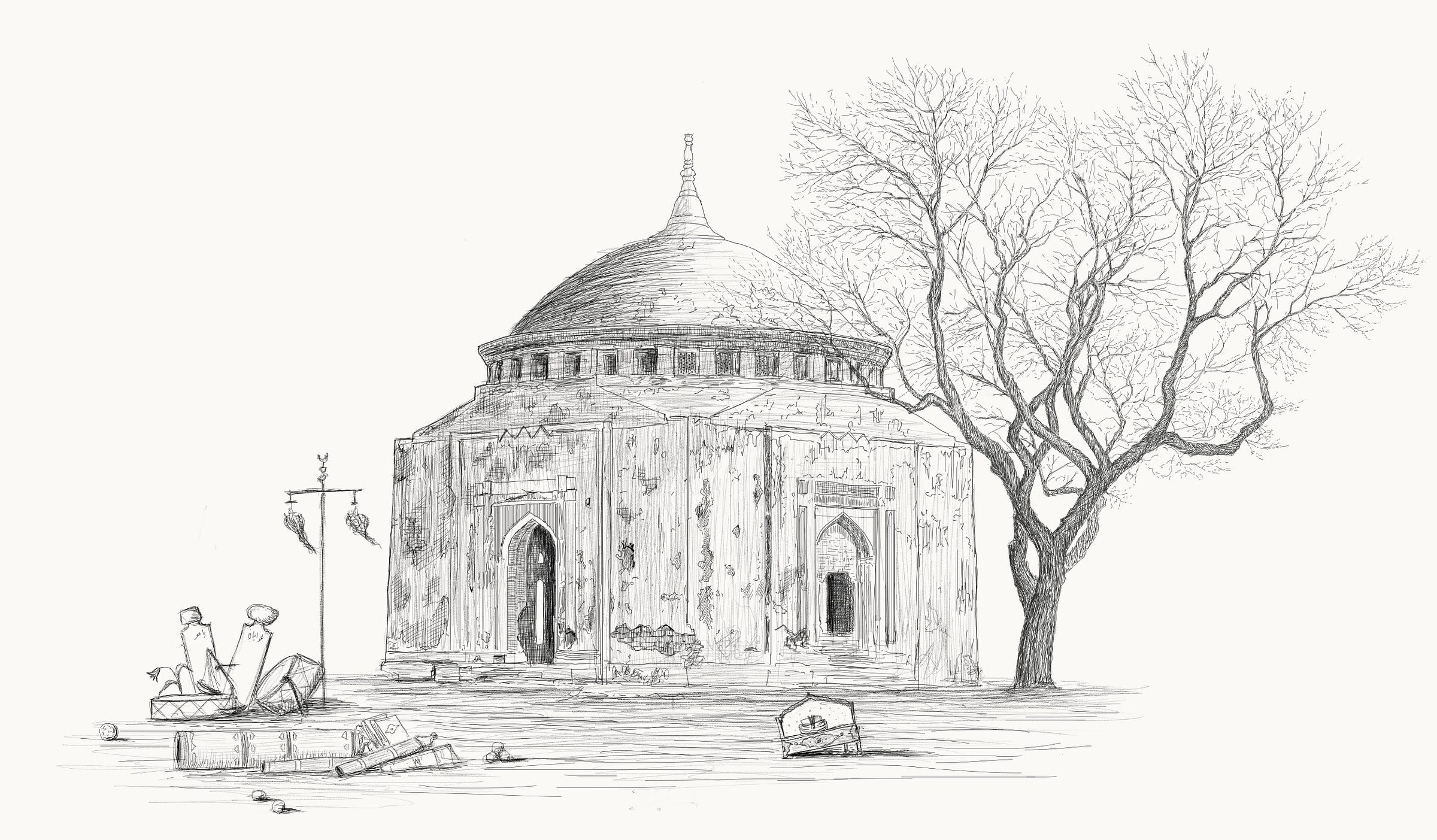

This dawned on me last year in the wilderness of Khuldabad, formerly in the princely state of Hyderabad but now in India’s western state of Maharashtra, as I looked upon a magnificent but derelict Turkish mausoleum. Completely abandoned and standing in the middle of nowhere, the great structure looks like an absurd anachronism.

It was built, however, for the last Ottoman Caliph, Abdulmejid II, although he wasn’t ultimately buried in India. I spent a year investigating and piecing together the forgotten story behind this mausoleum’s construction: the union of two of Islam’s greatest houses in the 1930s, a grand scheme to change the course of global history that ultimately failed.

The Post-imperial Caliphate

As a measure of India’s importance in the early twentieth century, the subcontinent was at the centre of the British Empire’s engagement with Islam. During the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913, through the Great War and the occupation of Anatolia, Indian Muslims influenced and often restrained British policy.

They then helped to save the Caliphate after the Ottoman Empire’s demise. When the fledgling Turkish state did away with the Ottoman Sultanate in November 1922, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk told the Grand National Assembly that it was unable to abolish the Caliphate: the Assembly “cannot decide by itself on behalf of the entire Islamic world, my good sirs”, since the “holy office of Caliph is a sacred position that involves the entire Islamic world.” Most concern for the office, of course, was directed from India.

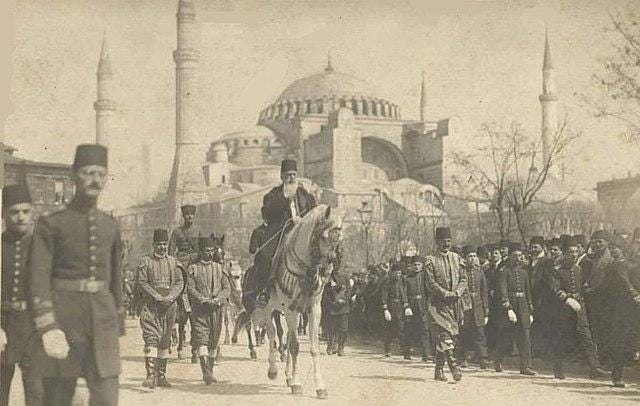

Crown Prince Abdulmejid - one of the most cultured of his dynasty, as a talented painter, musician and poet - claimed the Caliphal title in Istanbul. This was a radically reconstituted Caliphate: with no Empire or Sultanate, the Caliph was elected by the Assembly, although the Caliphate derived its true legitimacy, in Abdulmejid’s eyes, from the support of the world’s Muslims. This unprecedented settlement was short-lived. Once Türkiye was declared a Republic in 1923, Kemal and his government decided that the Ottoman Caliphate was a fundamental obstacle to the nation’s coherence and march toward modernity. It had to go.

On 3 March 1924, the Grand National Assembly abolished the 1,300-year-old institution that claimed successorship to the Prophet of Islam. Indian intellectual Sayyid Ameer Ali proclaimed it a disaster for civilisation that would “cause the disintegration of Islam as a moral force”. In London, The Times told its readers that in that age of dynastic downfall and the rise of radically new political orders, “no single change is more striking to the imagination than is this: and few, perhaps, may prove so important in their ultimate results”.

In Türkiye, all things Ottoman were quickly designated relics; by 8 March it had already been decided that the Topkapi Palace would become a museum. The Republic declared war on everyone who sympathised with the Ottomans. Suspected dissidents accused of opposing the Caliphate’s abolition were hauled before the dreaded (and dubiously-named) “Tribunals of Independence” to be tried for treason. The government put the Ulema under intense surveillance, and over the next few years, the madrasa apparatus was comprehensively dismantled and the Sufi orders criminalised. As for the imperial family, they had been bundled onto the Orient Express and expelled from the country as soon as the Caliphate was abolished. Other elites either went into exile, kept a low profile or remarkably converted - overnight - into avowed Kemalists.

Dissent certainly existed and occasionally turned into open revolt. In February 1925 a major rebellion erupted in Kurdish districts in the southeast. Thousands of Kurds, led by the dervish and tribal leader Sheikh Said, took up arms against the government. They demanded the restoration of the Caliphate and an end to what they saw as anti-Islamic reforms and a zealous Turkish nationalism. The rebellion was swiftly put down by Ankara’s military might - including aerial bombardment. The Sheikh himself was executed, along with thousands of his comrades and supporters.

Union of the two Houses

I was intrigued about what Abdulmejid did once he was exiled to Europe. Had he really taken the abolition lying down? Quite the opposite, it emerged: denying that the Assembly had the authority to end the Caliphate, just days after the abolition Abdulmejid appealed to the Islamic world from his Swiss hotel to support and restore the institution in a new form, reasoning that that “it is now for the Mussulman world alone, which has the exclusive right, to pass with full authority and in complete liberty upon this vital question.”

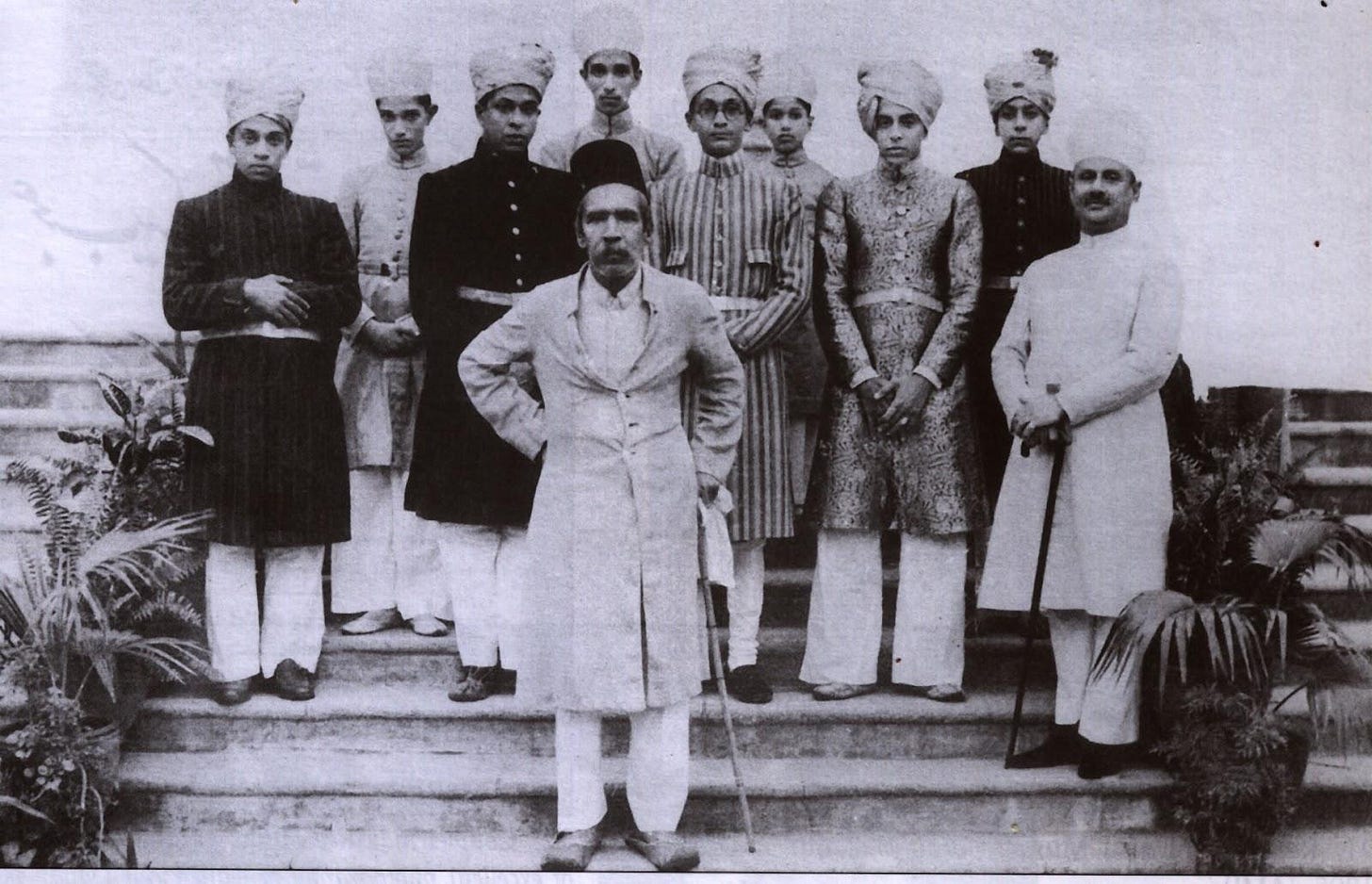

But the Ottomans had barely any money. Help came from India - from the fabulously wealthy Asaf Jahi dynasty who governed Hyderabad, a rapidly modernising princely state the size of Italy, under indirect British oversight. Its attar-scented palaces proclaimed all the grandeur of Indo-Islamic culture; the extravagance of its courtly life was legendary. The seventh Nizam, Osman Ali Khan, was proclaimed in the 1930s to be the richest man in the world: Henry Ford and his son had a combined fortune of less than half the value of his jewels alone. The billionaire ruler, himself a talented poet, procured magnificent Mughal miniatures and commissioned British Muslim thinker Marmaduke Pickthall to translate the Qur’an into English. Hyderabad’s capital city was a hub for Indian Muslim statesmen and thinkers from across the Islamic world. The Nizam also injected new life into the old high culture: classical singers and Qawwali masters frequented the royal court, performing mystical poetry to the beat of the drum and the gurgle of the water pipe.

Hyderabad had a presence beyond Indian shores, too. The Qu’aiti Sultanate, a large region in the southern Arabian peninsula, was governed from Hyderabad as a vassal state. The Nizam’s polity was fast becoming not just the cultural successor state to the Mughal Empire but a centre of the Islamic world. In this context, the Nizam became benefactor to the deposed Caliph, who settled down with his family in a seafront villa on the French Riviera.

In 1931 Caliph Abdulmejid launched a scheme with Maulana Shaukat Ali, a legend of the Indian independence movement, focused on the World Islamic Congress in Jerusalem. The conference, which Ali had initiated with the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem and was scheduled for December that year, aimed to draw Muslim notables and leaders from across the Islamic world. Abdulmejid planned to travel to Jerusalem and address the conference to shore up support for the Ottoman Caliphate. The scheme was disrupted once Turkish spies caught wind of it and lobbied the British to announce they would deny the Caliph entry to Palestine. The congress failed, although it was a watershed moment in establishing the Palestinian struggle as a global Islamic cause.

The Caliph, however, had another plan in the works. In October of that year, Shaukat Ali and Marmaduke Pickthall successfully brokered a marriage between Abdulmejid’s daughter Princess Durrushehvar and Prince Azam Jah, the Nizam’s eldest son and heir apparent. The wedding took place in Nice in November. Around the world, interested parties were aware of the political implications, from the Turkish government in Istanbul to the Urdu press in Bombay, and from English visitors in Hyderabad to American journalists in Nice. Before the wedding, TIME magazine reported that “Should these young people wed and have a man child, temporal and spiritual strains would richly blend in him. He could be proclaimed 'the True Caliph'.”

Abdulmejid himself announced that the wedding would “unite two Muslim dynasties by the intimate ties of family love; an event which cannot fail to have a very happy repercussion on the whole Muslim world.” Days after the marriage, the headlines in Bombay’s Urdu papers announced that the union foreshadowed the restoration of the Caliphate, based on briefings from Ali. The resulting furore led to the British Raj forcing the Nizam to cancel a plan to have the Caliph visit Hyderabad.

The Ottoman Succession

This alliance between the Ottoman and Asaf Jahi dynasties represented the union of Islam’s Caliphal dynasty with its wealthiest - of the west and east of the Islamic world, of both Ottoman and Mughal legacies. It also helped establish Hyderabad’s status as a “sort of capital city for all Muslims”, as Pickthall described the Nizam’s city. In 1933, Princess Durrushehvar gave birth to Prince Mukarram Jah, the grandson of both the Caliph and the Nizam. While his grandson was still a child, the Nizam privately informed his inner circle that Prince Azam Jah, his son and Hyderabad’s heir apparent, would no longer become the next ruler. Instead, he would be cut out of the line of succession in favour of his own son, Mukarram Jah.

The last Ottoman Caliph died in 1944 in wartime Paris, in almost total obscurity. Yet still he had hope for the future. I studied confidential messages sent between British officials and politicians - including the Viceroy of India - in the aftermath of his passing, as well as the writings of Hyderabad’s Prime Minister. They establish that Abdulmejid, writing his will in Paris, had intended for the Caliphal line to pass through the Asaf Jahi dynasty in Hyderabad. As long as this was kept a secret, the British resolved, there was no need for them to intervene; they would soon leave India and the succession was unlikely to concern them. What the Nizam himself wanted is unknown, but English travel writer Rosita Forbes, who was toured around Hyderabad’s capital by then-Prime Minister Sir Akbar Hydari in 1939, might have had it right when she wrote that the Asaf Jahi dynasty was “irrevocably allied with the fountain-head of orthodox Islam and committed to the principle of the Caliphate”.

If India had become a federation after British rule ended, it is plausible that Hyderabad could have been a powerful and autonomous state. In those conditions, Abdulmejid’s grandson Prince Mukarram Jah would have been better placed than anyone to claim the Caliphal title once he became Nizam. The Indian subcontinent could have become home to the seat of the global Caliphate, a centre of prestige and power in the Islamic world.

How would this have worked, since Muslims were a demographic minority in the subcontinent? Mahatma Gandhi and other Hindu leaders, supporting the Khilafat Movement back in 1919, had recognised that Islamic politics allowed India to greatly enhance its geopolitical standing. It was using the same logic that the Republic of India would later aim to join the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, although Pakistan thwarted its attempts to do so. This indicates that a federal India, which was quite possible as late as 1946, could have comfortably used Hyderabad’s Asaf Jahi dynasty to boost its influence and soft power in the Islamic world.

Equally, however, it is possible that a federation would have led to civil war in the subcontinent, or that most Muslims in the world would have rejected or simply ignored an Ottoman Caliph in Hyderabad. We will never know. Ultimately, Partition secured the end of Asaf Jahi rule in Hyderabad and carved up the Indo-Islamic world. The resulting independent state of Pakistan was vastly smaller and weaker than its neighbour, and destined to split in two again in 1971; Muslims in the new India, meanwhile, were left an unprotected and smaller minority. The Congress government could never allow a large and wealthy princely state to persist within India’s borders. As Partition unfolded in 1947, the Nizam’s attempt to secure his state’s independence was doomed.

The Fall of Hyderabad

The Indian army ultimately invaded Hyderabad on 13 September 1948. The aftermath was apocalyptic. 40,000 people (mainly Muslims) were massacred, according to a report commissioned and then buried by the Indian government. Many believed the number was much higher. Scholar Wilfred Cantwell Smith, who visited Hyderabad in 1949, thought that anywhere between one-tenth and one-fifth of the male Muslim population might have been killed. He noted that some “estimates by responsible observers” held that the true death toll was close to 200,000.

Muslims were purged from Hyderabad’s government and administration. The Indian army rounded up and detained 17,000 civilians - again, mostly Muslims. The state’s cosmopolitanism was also quickly destroyed: up to 25,000 Arabs were rounded up, along with thousands of Pathan and Afghan migrants. They were held in detention camps and over 20,000 were eventually deported. The Indian invasion, concluded the late historian AG Noorani in his masterpiece The Destruction of Hyderabad, “was the annihilation of a certain way of life, the uprooting of a people, and the sweeping away of a culture, swiftly and almost completely.” It was also the final blow for the Ottomans. Plans to fly the Caliph’s body over and bury him in the Nizam’s dominions were abandoned. His wish for the future of his lineage was well and truly dashed. And his mausoleum was left desolate in the wilderness, where it still stands to this day.

For decades, the story of the scheme for an Indian Caliphate has been consigned to near oblivion. But it is a history of great importance. It should reframe our understanding of the early twentieth century in a way that illuminates the Indian subcontinent’s forgotten former prominence within the Islamic world. Moreover, it is the story of the downfall of two old Muslim elites amid the creation of new nation-states. The twentieth century saw the near-total destruction of the Islamic world’s old cosmopolitan elite network, as ruling classes in several countries were dismembered and replaced. The consequences for the populations they had governed were monumental.

The fall of the Ottomans paved the way for a new Middle East - of new nation-states and novel conflicts to go with them. In that context, the plan to tie the House of Osman’s future to Hyderabad was a last-ditch attempt to salvage the Ottoman legacy, preserve some continuity between the old and new eras and establish deeper connections between far-flung regions of the Islamic world. The key players in the story - the last Caliph, the seventh Nizam, intellectuals Maulana Shaukat Ali and Marmaduke Pickthall - weren’t simply tired restorationists or quirky traditionalists. Important to study, they were part of a series of attempts to fashion a new order for Muslims in the twentieth century.

Writing in exile in 1924, Caliph Abdulmejid described himself, quoting Shakespeare's Hamlet, as suffering the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune”. But unlike the despairing Danish prince, he insisted, he was still “hearty, with a clear conscience, a strong faith”.

Imran Mulla is a journalist at Middle East Eye in London, before which he studied history at the University of Cambridge. His book ‘The Indian Caliphate: Exiled Ottomans and the Billionaire Prince’ is set to be published this December by Hurst & Co. You can follow him on X at @Imran_posts.

You can follow Kasurian on Substack Notes, Instagram, and Twitter/X for the latest updates.

All art has been custom-drawn for Kasurian by Ahmet Faruk Yilmaz. You can find him on Instagram and X.

This is mostly wishful thinking alternate history. You're ignoring the impact of the British and colonialists and most of these characters were irrelevant puppets. Caliph in a Swiss hotel room lol

India's partition... perhaps the greatest mistake in the collective Muslim experience.