Elephants, Rockets, and Tiger Statecraft: Tipu Sultan the Moderniser

Tipu's modernisation project nearly brought down the British in India. His eventual defeat holds lessons for us today.

The rise of European imperialism is remembered as a humiliation for Islamic civilisation. The great Muslim empires were unable to confront Western military might in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, lacking the centralisation, resources and technology with which to compete with European industrial strength. In India, the armies of the crumbling Mughal Empire were no match for the well-oiled fighting machine of Britain’s East India Company. The Ottomans made a belated attempt to modernise but ultimately failed, with the First World War dealing the fatal blow at the dawn of the last century.

Muslim traditionalists, however, strongly dispute the idea that the Islamic world floundered and fell behind, arguing instead that the modern West was an aberration and that, inspired by the Enlightenment, European empires developed outrageous and inherently immoral technologies and forms of governance. Muslim attempts to play catch-up with the West were doomed to fail because Islam, they claim, is incompatible with modernity.

This narrative has proven powerful and seductive since it neatly absolves Islamic civilisation of having to reckon with failure. It is also an increasingly popular position among young Western Muslim intellectuals. But this narrative has allowed a blinkered view of the past three centuries to develop.

In truth, some Muslim rulers bucked the trend and participated in modernisation, nearly disrupting the ascent of the European empires. While they may be remembered as heroes, their significance is often little-understood. These were ‘modernisers’, but not the ones we typically think of when that term is mentioned. They were statesmen who adopted modernity in the form of new science, military strategies, and bureaucratic technologies, which they comfortably integrated into their own worldviews.

One of the most significant such figures was Tipu Sultan, ruler of the South Indian kingdom of Mysore. In the late eighteenth century, this extraordinary figure nearly altered the trajectory of the British Empire by bringing the British East India Company to its knees.

Tipu Sultan is not exactly a forgotten figure. In Pakistan, he is lionised as a great Muslim hero, although he is rarely studied outside of academic circles. In India, meanwhile, he looms large in the Hindu nationalist imagination. While old-school secular politicians and intellectuals traditionally hailed Tipu as the first great hero of anti-colonial Indian nationalism, today Hindu nationalists revile him as the archetypal Muslim villain.

Often known by contemporaries as “Citizen Tippoo”, he allied with the French and made friends with Napoleon. Infamous for his gruesome wartime atrocities, he was known as the “Tiger of Mysore” - partly due to his prowess in warfare, and partly because his elite fighters dressed in tiger-striped uniforms. Tipu built his kingdom’s power and state capacity to an extraordinary level, forming a modern Western-style army that deployed military technology more advanced than anything the British had.

Ultimately, it was Tipu’s failure in diplomacy, rather than a lack of military or technological prowess, that brought him down. As he became increasingly isolated, the British could bring greater resources and armies to bear and eventually defeated him. Yet Tipu Sultan’s incredible rule stands as an essential example of a response to colonialism that defies the usual prejudices about Muslims in the modern era - one that sought to internalise advances in statebuilding, military technology, and the economy on its own terms.

Modernising Mysore

Haidar Ali, Tipu’s father, laid the groundwork for his son’s success. He ruled Mysore as a nominal province of the Mughal Empire from the 1760s, having emerged from its military ranks to depose and replace the ineffectual ruler, Wodiya Raja. Haidar set about diligently expanding Mysore’s army and invading neighbouring polities. He and Tipu, then only a teenager, hired French officers to train Mysore’s army and established a navy commanded by a European seaman.

In 1767, Haidar launched an assault on the East India Company east of Bangalore. The British, used to easy victories, were stunned to be confronted by an army of around 50,000 men – 23,000 of whom were cavalry – armed with cutting-edge rifles and cannon. They were particularly shaken to realise that the enemy’s artillery was more advanced than their own, with a far longer range.

Strategically, too, the Company was no match for Mysore. Seventeen-year-old Tipu was crucial to the war strategy, leading an implausible raid behind Company lines into Madras, where he set about looting and destroying its Georgian villas. In the end, the British were forced to sue for peace.

This was just the beginning. Time and again, Tipu’s armies fought and defeated British-led forces. In 1782, he led an army that decisively crushed a British column outside Tanjore. The next year, he ambushed a Company army by the Coleroon river. A massacre followed.

When Haidar Ali died shortly afterwards in 1783, Tipu was 33 years old and a statesman in waiting (he was also “uncommonly well-made, except in the neck, which was short”). His father, on his deathbed, had ordered him to devote his efforts to confronting the Company: “The English are today all-powerful in India,” he declared. “It is necessary to weaken them by war.”

The defining feature of Tipu Sultan’s rule was his ruthlessly selective adoption of his enemy’s strengths and tactics. While many Muslim modernists of the era are remembered for their infatuation with European high culture, such as Ottoman obsession with European music, suit jackets, and baroque architecture, Tipu took a different path. Indeed, in many respects, he was a quintessential Indian ruler. He wore a kurta, a silk brocade coat and a range of often absurdly elaborate turbans. A highly cultivated intellectual, his library boasted over 2,000 volumes in several languages. He loved music and dance, and composed poetry in Persian and the Dravidian language of Cannada.

Tipu’s religious sensibilities were also typical of Indo-Islamic elites: a devout Muslim, he was deeply interested in Hinduism, and made his troops bathe in holy rivers “by the advice of his [Brahmin] augurs”.

At the same time, Tipu embarked on a modernisation campaign that was unprecedented for any Indian ruler. He expanded Mysore’s state capacity, imported French industrial technology, introduced a sophisticated irrigation system and built dams. He developed water power-driven machinery. He even had silkworm eggs brought to Mysore from southern China and established a sericulture industry. British observers begrudgingly described the sultanate as “well cultivated, populous with industrious inhabitants”, and with “cities newly founded and commerce extended”.

Tipu established trade centres across India’s western coast and beyond. His state-owned trading company built factories in the Persian Gulf, with the most important of these located in Muscat. Mysore exported timber, sandalwood, ivory, and cloth to the Gulf, and imported pistachios, copper, and chinaware. In Muscat, European merchants had to pay a 5% duty, while most Indians paid 8%, and Arabs paid just over 6%. In contrast, Mysore’s merchants paid only 4%.

The Stuff of British Nightmares

Most significantly, Mysore’s military might turned the tide against the East India Company. As historian Christopher Bayly writes, Tipu’s strategy was to fight “European mercantilist power with its own weapons: state monopoly and an aggressive ideology of expansion.”

By 1786, Tipu’s inventory contained 300,000 firelocks, 22,000 pieces of cannon, 11,000 horses, and some 700 elephants. Most extraordinarily, Mysore developed the world’s first iron-cased war rockets, which were launched from bamboo or metal frames at enemy soldiers up to 2,000 metres away. Tipu’s rockets, which killed thousands of the Company’s troops, would later lead to Britain’s Royal Woolwich Arsenal establishing a research programme to study Mysorean rocket cases, ultimately using their research to develop the rockets they would deploy with great success against the French in the Napoleonic Wars.

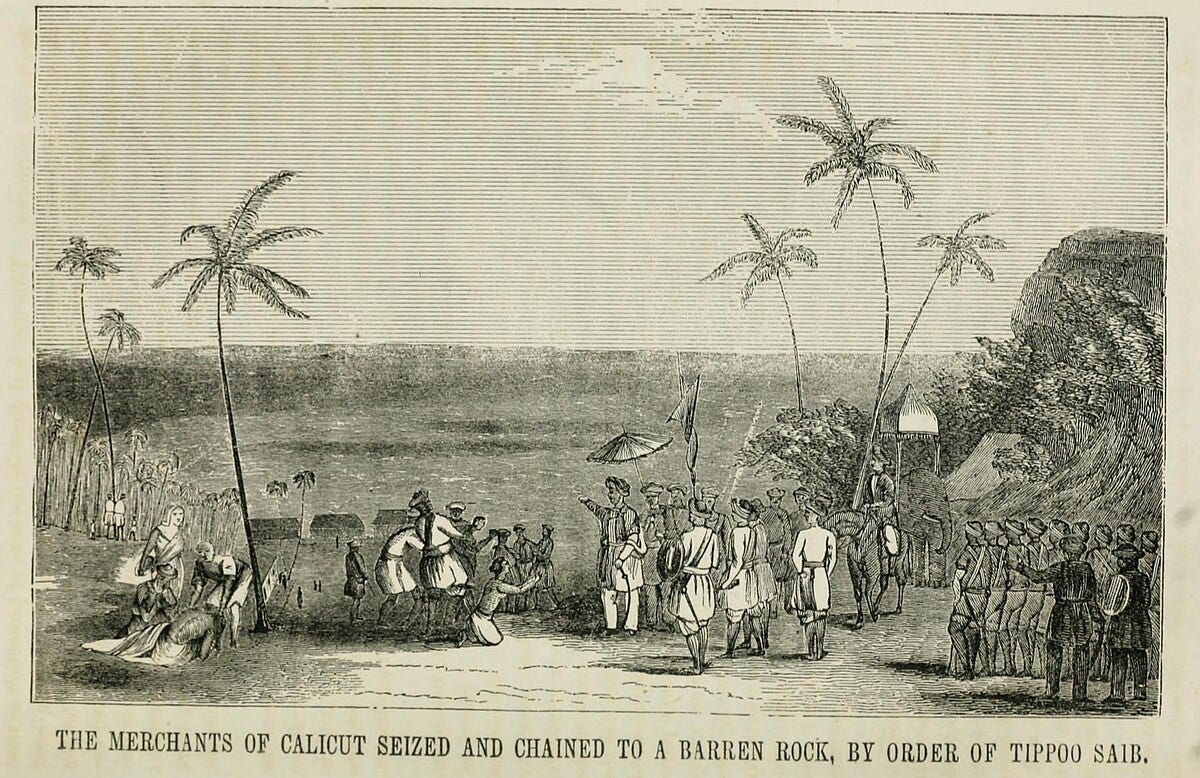

For two decades, Tipu Sultan haunted the British consciousness. He was the Company’s most loathed and feared menace. Tipu’s penchant for the theatrical contributed to this, including his elite sepoys who showed up to battle in tiger-striped uniforms. Colonial propaganda pushed by the Company’s Governor General Lord Wellesley portrayed Tipu as a savage brute, monstrous towards Hindus and Britons alike, and driven by Islamic fanaticism.

While this was largely fictional, the real Tipu did show terrible cruelty in war, and to a highly unusual degree by the standards of his own time. He earned something of a reputation. In particular, a great battle at Pollilur in 1780 caused shockwaves in Britain and seemed for a time to represent the beginning of the Company’s fall. An entire army was slaughtered, and Mysore captured one in five of all British soldiers in India, 7,000 British men, as well as an unknown number of women. They were taken to Tipu’s formidable island fortress of Srirangapatna, whose defences were designed by French engineers. British regimental drummer boys were forced to dance for Tipu’s court, and many soldiers were forcibly circumcised and converted to Islam.

While Tipu never dressed like an Englishman, more than a few Britons emerged from his captivity clad in kurtas and addicted to hookahs. After a decade in captivity, the prisoner James Scurry found he could no longer use a knife and fork or sit in a chair. His English was “broken and confused, having lost all its vernacular idiom”, and he despised English clothes. For the British public, this was the stuff of nightmares.

Among Tipu’s terrible policies in war was that he destroyed temples and churches in conquered territories. Portuguese missionaries recorded one particularly gruesome episode in which “he tied naked Christians and Hindus to the legs of elephants and made the elephants move around till the bodies of the helpless victims were torn to pieces”. But this was not driven by any religious fanaticism. In fact, Tipu enthusiastically patronised temples within his own domains. On one occasion, when the Marathas (a Hindu power) raided and damaged the magnificent temple of Sringeri in Mysore, Tipu sent money and grain to the temple and warned that “people who have sinned against such a holy place are sure to suffer the consequences of their misdeeds… Those who commit evil deeds smiling, will reap the consequences weeping.”

He was also tremendously popular with his subjects, who were predominantly Hindu. After Tipu’s death, the British found that his “confidential Hindoo servants” reported he had been a “lenient and indulgent master”.

The ‘Citizen Prince’

To expand his range of allies against the British, Tipu Sultan sought Ottoman support and recognition, but none was forthcoming. He had much more success with the French, whose East India Company competed with the British for dominance in the subcontinent. This was classic Tipu Sultan: a cynical and strategic alliance with a European power for his own ends. The French Revolution in 1789 did nothing to damage the relationship – in fact, Tipu established warm relations with Napoleon Bonaparte. The British, for whom this was an unbearable alliance, took to denouncing “Citizen Tippoo”, combining their loathing of the ruler with a healthy dose of Francophobia.

A Company diplomat, Major William Kirkpatrick, claimed that in May 1797, Mysore’s French troops established a Revolutionary Jacobin Club in Srirangapatna, which hoisted the tricolour flag. Kirkpatrick described to his British compatriots how a Jacobin maypole labelled ‘the Liberty Tree’ was planted, while French soldiers pledged their allegiance to the Republican constitution and swore “hatred of all Kings, except Tipoo Sultan, the Victorious”. Then at Srirangapatna’s parade ground, the “Citizen Prince” was said to have declared France to be Mysore’s “sister Republic”, and ordered an enormous salute from 2,300 cannon, 500 rockets and unnumbered musketry.

In reality, Tipu was no genuine Republican and cared nothing for Rousseau or Robespierre. The club was unlikely to have actually been given the “Jacobin” label, and its papers, which record that Tipu adopted the paradoxical title of “Citizen Prince”, may well have been fabricated by the British. Tipu engaged with European ideas, as much as European technology, only on his own terms.

Decline and Fall

The victory of the Company in India came with Tipu’s downfall in 1799. Having fought four major wars against the British, Mysore’s ruler had significantly slowed their ascent and forced them to fight tooth and nail for dominance. Largely because of Tipu, the British had lost their technological superiority. Nor did they have any administrative edge. Mysore had successfully closed the gap.

Ultimately, then, it was neither technological inferiority nor British brutality that secured Mysore’s defeat, but rather a staggering failure of diplomacy. This was Tipu’s great flaw. His father, Haidar Ali, had allied with three major powers – the Maratha Confederacy, Hyderabad and the French Company – making it impossible for the British to mobilise the powers that surrounded Mysore against the kingdom.

Tipu, by contrast, broke his alliances with the Maratha Peshwa and the Nizam of Hyderabad, and by 1786, he was waging war against both. Mysore’s aggressive expansionism terrified both rulers to the extent that they agreed to form a Triple Alliance with the British to bring Tipu down. In 1789, Tipu launched yet another war, this time against southern Travancore, whose Raja had entered a pact with the Company. By this point, Tipu had even proclaimed independence from the skeletal remains of the Mughal Empire, denouncing Emperor Shah Alam as “a mere cypher”. There would be no help from any Mughal army.

Still, Mysore demonstrated its superiority on the battlefield. A weary Major James Rendell noted in December 1790 that the “rapidity of Tippoo’s marches was such that no army appointed like ours could ever bring it to action in the open country.” But this only did so much against the Triple Alliance, which defeated Tipu in 1792 in the Third Anglo-Mysore War by besieging Srirangapatna and forced him to sign away half his kingdom in a humiliating treaty. “Know you not the custom of the English?” Tipu wrote imploringly to the Nizam. “Wherever they fix their talons they contrive little by little to work themselves into the whole management of affairs.” It was too late; the Nizam remained allied to the Company.

By this point, the Maratha Confederacy was in decline, and elite Indian financiers saw the Company, which controlled the revenues of Bengal and profited from the China trade, as the most reliable investment. This proved decisive. As the historian William Dalrymple writes in his monumental study of the Company’s ascent, The Anarchy: “In the end it was this access to unlimited reserves of credit, partly through stable flows of land revenues, and partly through the collaboration of Indian moneylenders and financiers, that in this period finally gave the Company its edge over their Indian rivals.”

Remarkably, however, Tipu fought on, famously proclaiming that “I would rather live a day as a tiger than a lifetime as a sheep”. His last hope was Napoleon, and in December 1797, he sent an embassy to Paris asking for the Emperor’s help. But Napoleon’s army was descending on Egypt. In April 1798, he assured Tipu from Cairo that he would come to Mysore’s aid after conquering Egypt, declaring that he was “full of the desire of releasing and relieving you from the iron yoke of England… May the Almighty increase your power, and destroy your enemies!”

But soon afterwards, in April 1799, Mysore was finally crushed when Wellesley’s army besieged Srirangapatna. In that final confrontation, Tipu “gave us gun for gun”, a British observer recalled. “Soon the scenes became tremendously grand, shells and rockets of uncommon weight were incessantly poured upon us.” Meanwhile, “the blaze of our batteries which frequently caught fire… was the signal for the Tiger Sepoys to advance, and pour in galling volleys of musketry.”

10,000 Mysorean troops fell in the final battle. The Tiger of Mysore himself ascended onto the battlements to fight. He charged at the sepoys and was shot in the left shoulder. His attendants begged him to surrender. “Are you mad?” he responded. “Be silent.”

Tipu Sultan wielded his sword, his final weapon, against a group of Company redcoats and killed a grenadier. Then another shot him through the temple, and he fell among his men.

With Tipu’s death, so ended the dream of the last sovereign Indian state. Tipu’s energetic reforms enabled Mysore to supersede the best of European military technology and military organisation in short order. His strenuous modernisation programme for Mysore’s army and economy was so successful that it had compelled even the British to play catch-up militarily, nearly preventing their takeover of India and potentially changing the course of world history. It also inverts the traditional narrative of an unstoppably widening technological chasm between the West and the rest.

Yet it was not enough.

There is great significance in the history of Mysore's extraordinary diplomatic failure. It was the inability of Indian rulers to unite (with most failing even to identify the threat posed by the East India Company until it was too late) that secured the triumph of the British in the subcontinent. However, Tipu’s reign also puts lie to the myth that the Islamic world suffered a permanent decline for three centuries, let alone for a millennium, as many claim. Serious decline in the Islamic world began only in the nineteenth century, when reformers ceased to engage seriously with Europe in the material realm and retreated to the world of culture and ideas, as with the Tanzimat movement in the Ottoman Empire.

Before this retreat, some Muslim statesmen remained dynamically engaged with the challenges that confronted them, the most significant examples being Tipu and Muhammad Ali Pasha (the nearly contemporaneous Ottoman governor of Egypt). Far from rejecting modernity or capitulating to Western ideas of what it should be, Tipu fashioned his own modernity. He had no philosophical anxieties about modern warfare or governance being immoral and un-Islamic, and his response to the rising power of Europe was to selectively adopt and adapt what he wanted from it.

The tale of the Tiger of Mysore serves as both a corrective measure to traditional narratives of decline and a warning on how even the most skilled statesmen can be undone by hubris.

Author: Imran Mulla is a journalist at Middle East Eye in London, before which he studied history at the University of Cambridge. His book ‘The Indian Caliphate: Exiled Ottomans and the Billionaire Prince’ is set to be published this December by Hurst & Co. You can follow him on X at @Imran_posts.

Artist: All art has been custom-drawn for Kasurian by Ahmet Faruk Yilmaz. You can find him on Instagram and Twitter/X at @afaruk_yilmaz.

Socials: Follow Kasurian on social media via Substack Notes, Instagram, and Twitter/X for the latest updates.

Further Reading

Bayly, Christopher. Indian Society and the Making of the British Empire. Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Dalrymple, William. The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company. Bloomsbury, 2020.

Manjunatha T. 'Military Modernization Efforts Under Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan'. International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research, Volume 6, Issue 5, September-October 2024.

Mohibbul, Hasan. History of Tipu Sultan. The World Press Private Ltd, Calcutta, 1971.

Qadir, Khwaja Abdul. Waqai-I Manazil-I Rum: Tipu Sultan's Mission to Constantinople. Aakar Books, 2005.

Sampath, Vikram. Tipu Sultan: The Saga of Mysore's Interregnum (1760–1799). Penguin Random House, 2024.

Sivasundaram, Sujit. Waves Across the South: A New History of Revolution and Empire. Harper Collins, 2021.