The Institution That Engineered a Culture

How science fiction built the Royal Society of Arts, Britain, and the modern world.

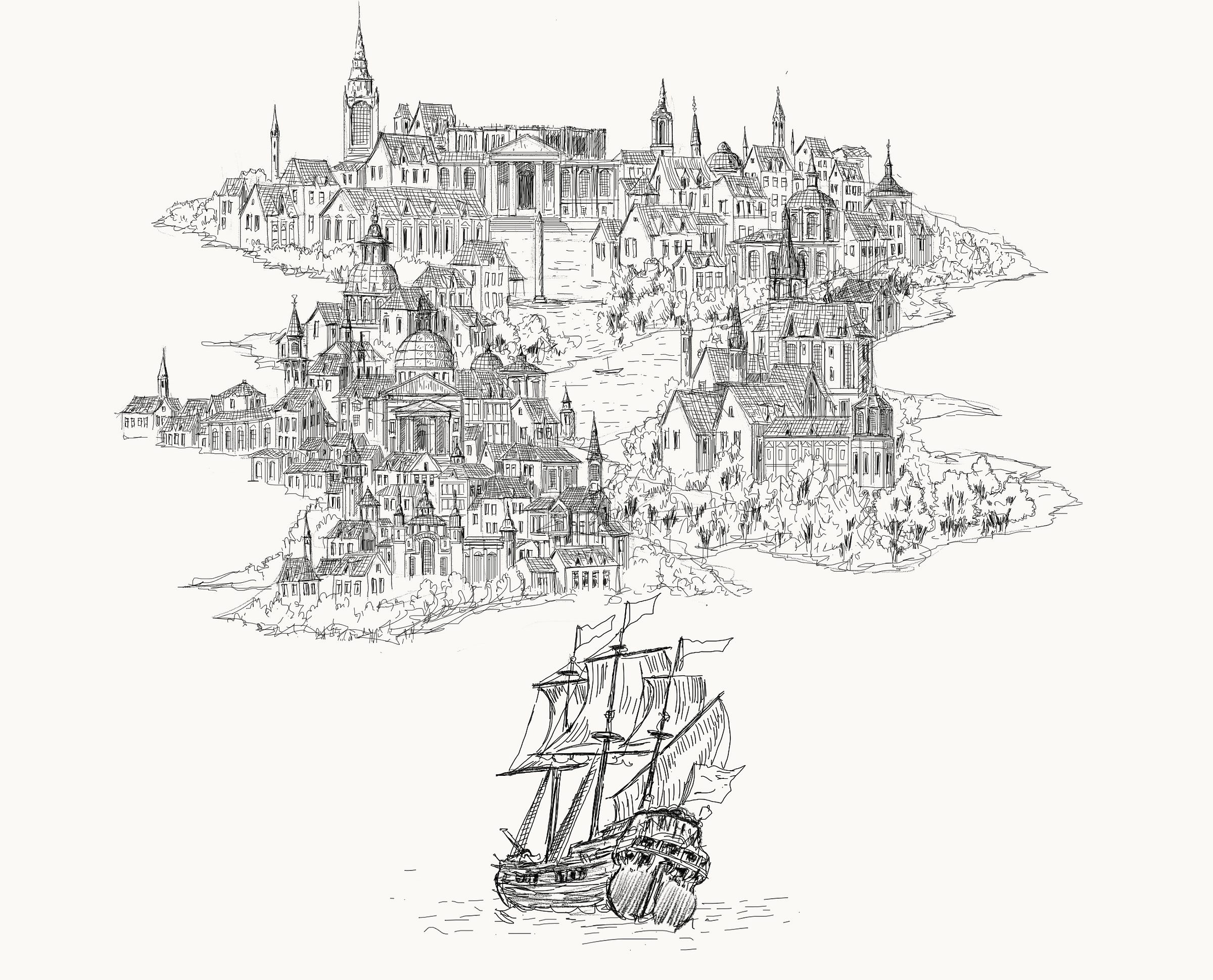

The Utopian Blueprint

Cultures of innovation are not accidents of history. They are consciously curated forces that embody risk-taking and obsession, the relentless application of trial-and-error toward perfection, and the persistent question: could it be better? A true culture of innovation also reflects Ihsan, acting with excellence and sincere intention. Without an Ihsan-guided culture of innovation, and the immense willpower and vision to improve civilisation, we default to a natural state of entropy.

Where do cultures of innovation come from? This question has become more pertinent as there is a prevailing feeling that culture has become stuck. Music, film, and art in general go through reboot after reboot. Scientific knowledge, too, suffers from this problem of diminishing returns. Between the turn of the 20th century and 1969, the world leapt from men on horses to men on the moon. Yet, in the past 50 years, no similar leap has been made. The institutions of culture and knowledge we have inherited seem to be in permanent decline.

Somewhere along the way, we lost our imagination. The problems of our age require bold institutional reimagining by reverse-engineering the culture of innovation that created the modern world as we know it. No example better illustrates this than the Royal Society of Arts, an institution born from utopian fiction that would transform Britain and, by extension, the world.

In the 17th century the great English polymath, philosopher and statesman, Sir Francis Bacon, dared to imagine a future in which knowledge would be systematically collected and applied to the improvement of all aspects of society. Bacon’s scientific view of knowledge was best represented by his statement, scientia potentia est – knowledge is power. As a devout Christian, Bacon saw divine purpose in the understanding of nature through science as a means of drawing closer to God and creating a more perfect society. It is in the pursuit of Ihsan that Bacon planted his utopian ideals in his seminal (and unfinished) work of proto-science fiction, The New Atlantis, which would inspire a new culture of innovation and change the world.

In The New Atlantis, a group of sailors find a utopian island kingdom in the mid-Atlantic called Bensalem (derived from Hebrew, meaning ‘son of peace’). The sailors find it inhabited by a religious nation with a sophisticated culture and level of technical knowledge unlike anything known in Europe or the Americas. At the heart of this kingdom was an educational institute called Solomon’s House, dedicated to “the knowledge of Causes, and secret motions of things; and the enlarging of the bounds of Human Empire, to the effecting of all things possible." To that end, the House had many wings, researching disease and health, light and observation, marine phenomena and water, soil and plants, and various creatures. It was out of this scientific pursuit of knowledge that the people of Bensalem were able to apply their learning to the creation of a healthier and moral society.

Although a fictional institute, Solomon’s House would inspire the creation of the modern research university and countless academies, societies, and foundations dedicated to the pursuit of scientific knowledge. At the heart of these societies and institutions lay the ‘new science’— the empirical method laid out by Bacon in The New Atlantis, which became an obsession of natural philosophers, scientists, and tinkerers over the 17th century. Out of that obsession sprang the Royal Society, one of the first and still-surviving institutions dedicated to the pursuit of natural knowledge.

While philosophers deliberated on abstractions, it would take a man of action to bring Bacon’s vision to life. This is how a utopian 17th-century science fiction book reimagined the role of knowledge in society and the form of institutions in which that knowledge was systematically collected and applied through persistent innovation, creating the cultural conditions that would make the Industrial Revolution possible.

Creating Solomon’s House

Bacon’s new science was emulated by 17th-century philosophers, scientists, and intellectuals across England, who now sought to verify fact through structured scientific experimentation rather than trial and error. Numerous societies were formed to deploy Bacon’s methodology at scale, such as the famous Royal Society of London for the Improvement of Natural Knowledge, which counted Isaac Newton among its ranks.

Yet, despite this prestigious membership and scientific accomplishments, the early societies fell short of Bacon’s vision. They concerned themselves solely with the advancement of knowledge, not the advancement of society. Their members were incentivised to cultivate intellectual prowess over applied and practical craftsmanship, and Bacon’s methodology became an end in itself rather than a means to improve society. This philosopher’s conceit, the belief that knowledge alone, without application, is progress, meant that these institutions would fail to realise the impact promised by Bacon’s ideas. It would take the vision of William Shipley to realise what Bacon had imagined a century earlier.

Born in 1715, Shipley was an artist by training. He seemed an unlikely candidate to build a pioneering institution that would shape British culture and knowledge for centuries to come, being a reserved man who rarely partook in the convivial elements of higher society. But Shipley was dismayed by the misapplication of Bacon’s ideas, seeing that existing institutions were collecting knowledge but failing to apply that knowledge to improve society. So, Shipley set about to do it. Where others saw abstract utopia, he saw practical possibilities.

To seek inspiration, Shipley studied Greek and Roman societies on how to create a culture of innovation from the ground up instead of relying solely on state or elite patronage. He learned that ancient societies had developed systems where the state, backed by revenue through taxation, could allocate money and incentivise cultural production through grants, monetary prizes, and other forms of patronage. It was in this model that Shipley identified the kernel of truth: a culture of innovation required patronage that funds production through private initiative.

In 1753, aged just 38, he founded the ‘Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce’. Shipley’s innovation was not in the Society’s mission but in its institutional design. Taking inspiration from the Greeks and Romans, he designed a subscription model that allowed members of the public to fund the institution’s activities, much like a state funds its public spending through taxation. In the 21st century, we are inundated with subscription services that cater to our worst instincts for pure consumption. In the 18th century, this was a pioneering financial model that could consolidate and leverage popular financial support by turning small and irregular donations into a persistent stream of revenue, to then be invested in the creation of culture.

Growth was initially slow, but for the next five years, Shipley put on exhibitions, shows, and competitions to attract both talent and patrons. He dedicated substantial time to networking with the English aristocracy, seeking trustworthy donors and influencing rising elites to adopt and potentially fund the cultural practices and artefacts incubated by his institution. Where early societies had been exclusive clubs for the intellectual elite, Shipley’s Society engaged the public directly. Women, barred from participating in most societies at the time, became frequent attendees and winners of the Society’s competitions.

By 1758, Shipley’s persistence had paid off. Membership of the Society had increased sufficiently such that a hundred ‘premiums’ (prize money deducted from membership’s subscription fees) could be issued as rewards in a diverse set of cultural competitions focused largely on drawing and painting. While initially focused on drawing and painting, the Society did not restrict itself to cultural activities. It adapted, rapidly expanding its mandate into the commercial realm.

The Society’s expanded breadth was strategically important in 18th-century Britain. War and trade were inseparable, and France was Britain’s arch-nemesis in both arenas in the 18th century. France was the cultural hegemon of Europe, and the British aristocracy imported French cultural affectations and products, lacking any equivalent indigenous cultural and material production. The Society set out to change this. Its earliest art competitions required that inspiration be taken from English history alone, consciously building a national aristocratic identity.

Having begun with cultural and economic production, the Society turned to providing auxiliary services to the English state during the Seven Years’ War against France, issuing subsidies for commodities like grain and meat, and funding innovations in artillery design, navigation, and shipbuilding. Here was Bacon’s vision in action, knowledge applied to real-world problems, from art to agriculture and war.

The sheer breadth of the Society was powered by its unbounded culture of innovation. With a mandate to fund and improve any aspect of society, the Society realised Bacon’s vision in a way his contemporaries had failed to do. In these endeavours, the Society endured failure more often than success. What was crucial is that these failures were seen as opportunities to understand the problems they were trying to solve, and to revisit their approach and try again from a different perspective or strategy.

In no small part, the Society was fortunate that its acclaim rose with that of England’s, as Britain defeated France in the Seven Years’ War and began its historical ascent. The Industrial Revolution would soon power Britain’s global conquests, and the Society would play a crucial role in shaping how that revolution unfolded.

What Goes Up Must Come Down

The 19th century was the age of industrial production: the mass production and consumption of goods, globalising cultural trends, and Britain at the heart of a burgeoning global empire connected by an international postal system and money exchange. As an incubator of culture and knowledge, the Society acted as a primary architect in the first wave of globalisation, guiding Britain’s transformation from a nation of craftsmen into an industrial powerhouse.

The Society’s crowning achievement came in 1851, when the Society hosted The Great Exhibition of 1851, also known as the Crystal Palace Exhibition due to the glass palace that housed it. This Exhibition was strategically designed to display the pinnacle of British scientific ingenuity, industrial power, and cultural influence in the world. It was also the first great international exhibition for industry that would inspire later World Fairs, and was sponsored by Schweppes, the world’s first soda company. In 1862, the Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky described the Exhibition as a representation of a utopic society, echoing, knowingly or unknowingly, the Society’s Baconian roots. The Exhibition was the high point not just of the Society’s influence but of Britain’s industrial, scientific and cultural power. It was under Cole that Prince Albert became president of the Society, further elevating its prestige. The Society’s success was extraordinary, and in 1908, it finally received the right to call itself the Royal Society of Arts, cementing its central place in British culture.

Britain’s transformation reached its zenith under the leadership of Henry Cole, who became the secretary of the Society in 1858. Before his leadership of the Society, Cole was a civil servant earning an additional income as a journalist, often approached for his expertise in the aesthetics of mass products. His introduction to The Society came through his expertise, being approached to serve as an advisor for The Society’s competition of applying art to manufactured goods to improve the public’s taste.

Cole was a charismatic innovator. He understood that tastes and fashions could be socially engineered and set about trying to shape British and international cultures. Although many of his efforts were a one-man tour de force, Cole took personal charge of recruiting members such as Herbert Minton, founder of the Mintons pottery company and Ramsay Hay, an interior decorator who repainted The Society's offices. Cole was also an inventor in his own right, introducing new designs for envelopes and stamps that came to define the postage system, and pioneering the first formal mass examinations to test competence that would later spread to schools, universities, and even the civil service. Under Cole, the Society also lobbied successfully in favour of patents and limited liability, essential for mass entrepreneurship and the burgeoning rise of capitalism.

As the Society accumulated these victories, the inevitable pull of entropy first began to show its signs. The Society that had engineered a new mass culture and industry eventually became a victim of its own success. The primary victim was craftsmanship, the very thing the Society had initially promoted. As Shipley, Cole, and their contemporaries had known, good design traditionally comes from below, from craftsmen engaged in hands-on mastery. While the Society’s members frequently quibbled on the relationship between craftsmanship and new technology, mass production had fundamentally altered that relationship.

As the Society became part of the fabric of Britain’s high culture, it experienced symptoms of decline. The decline became especially pronounced after World War II, when the Society began overzealously awarding fellowships and medals, financing them through massive bequests. For Shipley, membership had been dependent on the intention to create, not to coast off past legacies. But in the 20th century, prestige and bequeathments allowed the Society to live beyond its means, leading to a decline in the productivity, innovative capacity and skill of its ever-growing membership.

Yet, institutions can continue to function well beyond their golden age; decline is rarely a rapid descent into destruction. The Society’s survival became dependent on recognising and addressing its administrative burdens directly. Christopher Lucas, its secretary in the mid-seventies, accepted the Society’s survival depended on radical reform. In a bold move, Lucas gambled and sold the examination board that had become a drain on resources. The board now exists in the form of the OCR, one of the national examination boards in Britain. Lucas relied on ad hoc efforts to make up the lost revenue while intensifying his focus on the Society’s other activities.

The strategy has borne some fruit. Although at a more modest scale, the Society continues to benefit British society by incentivising and invigorating the public through small grants for specific social projects and creating local community banks in southwest England. However, it remains a far cry from the heyday of the 19th century and the Industrial Revolution. Like many institutions before it, the Society succumbed to entropy.

Back to Utopia?

The lesson of the Society is that culture is not made, improved or preserved by accident. It takes immense individual will and vision to forcibly advance civilisation. The culture of innovation incubated in the Society was so generative that what we come to associate with much of British culture today was consciously curated, sponsored, and elevated to national and global prestige by the Society. From international post stamps to London’s blue plaques, the Society has its fingerprints all over the aesthetics of Britain, one of the most influential nations in history. That an institution could have such an impact on culture runs against the popular assumption that culture is an organic process that “filters upwards”.

The Society would not have been possible without Bacon, whose desire to improve society through the application of scientific knowledge was his act of service to God and fellow man. In the New Atlantis, he produced a work of institutional fiction that has inspired centuries of progress. Shipley, driven to apply knowledge to the problems of his age, actualised Bacon’s vision. Cole transformed that vision into an engine of national identity and industrial might, reshaping British culture and, with it, the world.

Where have the cultures of innovation gone? Perhaps, just as in the 17th century, answering this question requires not only new scientific knowledge and technology but another work of visionary fiction that creates the utopian ideals, institutional innovations, and conviction to bring them into reality.

Burak Ömer is a financial markets professional based in Belgium. He previously studied applied mathematics & philosophy and is currently pursuing classical Islamic studies.

You can follow Kasurian on Substack Notes, Instagram, and Twitter/X for the latest updates.

All art has been custom-drawn for Kasurian by Ahmet Faruk Yilmaz. You can find him on Instagram and X.

Further Reading

Arts and Minds: How the Royal Society of Arts Changed a Nation - Anton Howes

The New Atlantis - Francis Bacon

I love this magazine already!