How Islam's European Elites Were Destroyed

A religious revival in Albania reveals a history of power and empire.

European Elites and Muslim Rubes

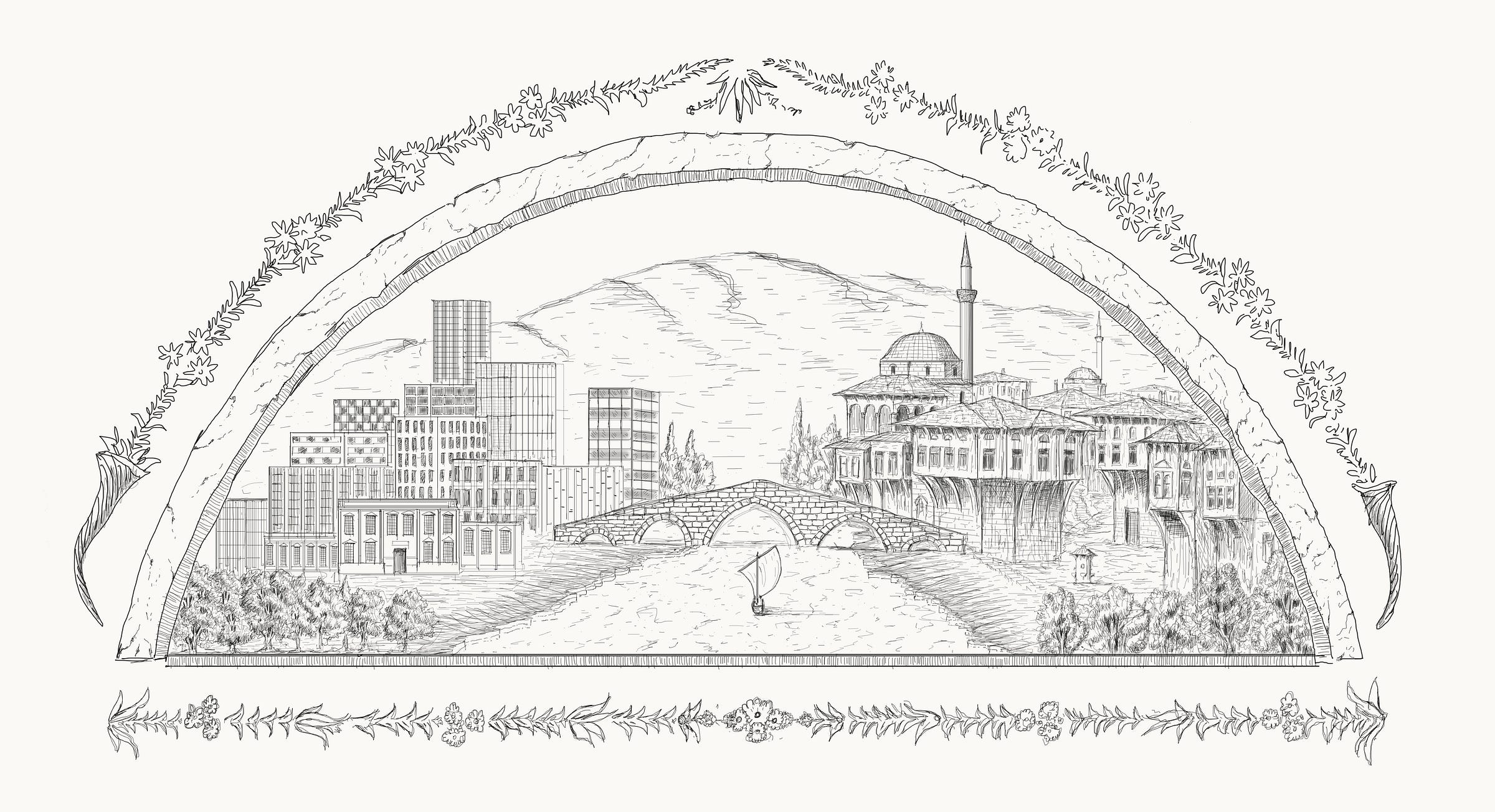

On 10th October 2024, Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama, alongside dozens of politicians and clerics from Albania and Turkiye, inaugurated the Namazgah Mosque in the centre of Albania’s capital, Tirana – now the largest mosque in the Balkans. Crowds gathered to witness the sight in the public plaza in front of the mosque, which abuts Albania’s parliament and the Tirana fortress atop a small hill in the city centre. Regional social media was flooded with drone footage of jubilant crowds on a warm fall day as clerics supplicated to God. That Friday, for the first time, the Namazgah Mosque’s loudspeakers joined the chorus of the city’s other mosques in calling the faithful to prayer.

Just a generation ago, the scenes unfolding at the Namazgah Mosque would have been unthinkable. Under the idiosyncratic Maoism of Albania’s paranoid and mercurial Cold War despot, Enver Hoxha, Albania was officially an atheist state from 1967 until 1990. As the communist regimes of Europe, including Albania’s, crumbled, the Albanian faithful of all religions emerged onto a desolate religious landscape.

The state apparatus’ zeal in suppressing religion had taken its toll. Decades of hiding Qurans and Bibles in the walls of homes, holding mawlids and masses in secret, and dynamiting sites of historical memory meant that as Albanians returned to their faiths, there were but a few tragic remnants from which they could build anew. When Albanian Muslims selected a new Grand Mufti in 1991, they appointed Hafiz Sabri Koçi, a spiritual leader of the Tijani sufi order and a figure from the pre-Hoxha era. The communist regime had abolished the position of Grand Mufti in 1967, compelling under police harassment the Grand Mufti of the time, Esat Myftia, to abdicate his role in public life. Even the construction of the Namazgah Mosque was compelled by a tragedy of the communist era – the previous main mosque of Tirana, the Old Mosque, had been levelled by Hoxha.

In recent decades, despite the indignities piled upon the faithful by Hoxha’s regime, and mirroring developments across post-communist Europe, there has been a religious revival in Albania. New places of worship have been built, public manifestations of religion are tolerated and sometimes sponsored by the state, and citizens are free to openly identify with and practice whatever religion they choose. Muslim Albanians can once again pray en plein air on Fridays and holidays, open schools and seminaries, and travel freely on pilgrimage to the Hejaz and for study at institutions in Turkey, Egypt, and Syria. The active participation of officialdom at the inauguration of the Namazgah Mosque shows that the resurgence of Islam’s importance in Albanian life is promoted, to an extent, by Albania’s political elite.

Despite the apparent elite patronage of Islam’s revival, Albania’s contemporary elites largely follow the French model of secularism, or laicité (a model replicated with gusto by the 20th-century elites of Turkiye, among other post-colonial regimes). Under laicité, religion is viewed as a private matter, salient only within one’s conscious mind and, if the state apparatus feels solicitous enough toward the sentiments of the faithful, within one’s own home. Under orthodox laicité, religious symbolism is marginalised in public life to guarantee freedom and neutrality, and the use of religious concepts and modes of reasoning is accorded little prestige or importance in society’s sensemaking institutions.

The predominance of laicité among Albania’s elites follows a pattern widespread in post-communist societies. The elite are at no great pains to present themselves as overly religious, whether they be Muslim, Christian, or otherwise. Instead, they view themselves as archetypal Europeans and envisage the governance of Albania as a project in fashioning a European state and society. Despite not being officially part of the European Union, EU-funded and affiliated institutions are pervasive, and EU flags festoon most government buildings. Children of Albania’s elite attend boarding school at Le Rosey and university at the London School of Economics or the Sorbonne; Prime Minister Rama, a Francophile, lived in France while pursuing his career as a visual artist and enjoys a close relationship with France’s President Macron, among other Western leaders.

Albania’s current elite has reproduced a stereotypical “Western” high culture, disseminated through the country’s cultural institutions, mass media, and political and educational systems, whereby high-status, elite values are equated with archetypal “European” values - politically liberal, socially progressive, and above all, secular. Whatever the personal convictions of the elite may be, their patronage of Islam is more a liberal-hearted concession to the bona fide beliefs of the populace than an expression of the elite’s preferred value system. Lacking meaningful elite patronage, the revival of Islam in Albania trundles along as a “low class” and purely bottom-up affair, which codes Islamic practice and belief as plebeian, un-European, and unfashionable.

Was it a foregone conclusion that the elite of this Mediterranean nation in the heart of Europe would be laique and impress secular values as good, desirable, and aspirational, and Islam as equally impoverished, uncool, and embarrassing? More importantly, has this always been Islam’s place, an import for mass consumption from an Agrabah-like land of sand dunes and Altaic nomads?

There is nothing predetermined about the path Albania has trod. Instead, the current state of affairs is the result of identifiable and concrete historical processes, telling the story of the fall of an old elite and high culture and their replacement with a new elite and high culture.

The Albanian Connection

From the early modern period (circa. 16th century) into the early 20th century, indigenous Albanian elites, both Muslim and Christian, played an active and prominent role in the Muslim world's politics, society, culture, warmaking, and diplomacy. They governed lands at the heart of the Ottoman Empire and decisively shifted Islam’s centre of gravity to Europe. More than merely expanding the reach of Turco-Persian dominion into Europe, Albania’s elites steered a process of cultural synthesis, creating a distinctly European, indigenously-inflected form of Islam. To this day, the monuments they left behind continue to stand as testaments to their sophisticated and cosmopolitan worldview as European Muslims. Delicate paintings of lush gardens, gleaming stone-clad cities, and fearsome galleons adorn the walls of the Et’hem Bey Mosque in Tirana and the Painted Mosque in Tetovo, a joyous expression of European baroque art in the context of Islamic sacred architecture.

The number of Albanian viziers, generals, aghas, damats and pashas is too great to count. Of the 292 grand viziers who served as the right hand of the Ottoman sultan across six centuries, 48 were Albanian, the second-largest group after the Turks themselves (who provided 140 grand viziers). The Köprülü family, of Albanian origin, alone provided six grand viziers and essentially ruled the empire in the Sultan’s place throughout the 17th century, reforming the Ottoman state and launching new wars of expansion that would only be checked by defeat at the gates of Vienna in 1683 (which resulted in the Sultan banishing the family from power). Albanians also left their mark on the imperial skyline of the imperial capital, Istanbul. The Sultanahmet mosque, sitting across the Hagia Sophia, was designed and built by the Ottoman Albanian architect, Sedefkâr Mehmet Agha, a student of the renowned master architect, Mimar Sinan.

No mere handmaidens of imperialism for the House of Osman, Albanian Muslim elites often rebelled and asserted their independence against the Ottoman sultans. They were an anchoring force unto themselves in the Islamic world. Ali Pasha Tepelena ruled over large swaths of the western Balkans in the early 19th century and famously befriended Lord Byron. Another example is Muhammad Ali Pasha; born in Kavala (now in Greece), he established a semi-independent kingdom in Egypt in the first half of the 19th century and would nearly overthrow the House of Osman. Under Muhammad Ali’s successors, Egypt won its independence, built a standing army, and began to urbanise and industrialise. Until the fall of the Muhammad Ali dynasty in 1952, the kings of Egypt maintained a distinctly Albanian identity, which they viewed as entirely congruent with their role as important nodes in the international network of Muslim aristocrats and royals.

Albanians also contributed to the intellectual life of the Islamic world. Sami Frasheri was a prominent intellectual in the 19th-century Ottoman Empire, writing on Ottomanism, Albanian nationalism, and the reform and renewal of Islamic civilisation. His son founded the Galatasaray football team and was president of the Turkish Olympic Committee in the 1920s. Hasan Tahsini, while intimately involved in the struggle for recognition of the Albanian language in the Ottoman Empire, was rector of the University of Istanbul and wrote what are considered the first Ottoman-language treatises on contemporary Western psychology and astronomy.

Christian Albanians also played an important role in the Muslim world but had a more tempestuous relationship with their Muslim suzerains. Christian elites maintained independent regional power bases and often clashed with local Muslim rulers and distant sultans alike. The Souliotes, Christian Albanian tribesmen, famously fought for Greek independence from the House of Osman and won several major victories in the name of Greek liberty.

Nevertheless, Albania had an elite class of indigenous Muslims who sat at the centre of Islamic civilisation and were paragons of its high culture. For almost half a millennium, Albania’s elites served, governed, defended, and expanded the Muslim world within and without the Ottoman Empire. In stark contrast, the Albanian elite today is a decisively secular and secularising force. Islam is relegated to the realm of necessary public ceremony and bona fide but decidedly unfashionable conviction for the declassé masses.

Unraveling Albania’s Muslim Elite

Exploring Tirana, one finds clues to understanding this profound transformation. How could belief in Islam and the history of Islamic civilisation go from motivating to embarrassing for the elite? Housed in a defunct communist-era bunker, Bunk’Art 2 is a museum documenting the atrocities of Albania’s communist regime. In the dank hallways of the bunker, you learn about the regime’s use of executions, torture, expulsion, concentration camps, and the extensive spying apparatus of the much-feared secret police, the Sigurimi. Entering into one of the final rooms in the museum, hanging in front of you are pieces of paper suspended from the ceiling by strings listing the names of those executed by the communist regime. You cannot help but notice hundreds of Muslim names: Mehmets, Fatimes, Abdyls and Bajrams.

A fifteen-minute walk from Bunk’Art 2, a plaque commemorating massacred intellectuals sits near the headquarters of Albania’s muftiate. Inscribed on the plaque are Alis, Mehmets, and Qemals. Several stately homes bear plates naming the pre-communist occupants, often prominent Muslim landowners and their extended families.

Through the tumult of the 19th and early 20th centuries, wars of nationalism forged homogenous nations from heterogenous transcontinental empires. In all of these cases clerics, teachers, aristocrats, doctors, intellectuals, industrialists and military officers were targeted for elimination by rival religious or ethnic groups – the idea was to destroy the “intelligentsia” who would sustain the group’s high culture, and therefore sap a group’s identity and beliefs of their salience and life-force. The baleful effects of these conflicts affected religious and ethnic groups throughout the Old World, and Albania was not immune to these global currents.

Bringing these scattered clues together creates a larger picture – throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Albania’s Muslim elite was systematically exiled, imprisoned, tortured and executed, their wealth seized and their institutions dissolved. Often, these incidents were tangential to wider conflicts, including the Balkan Wars, the Great War, and the Italian invasion of Albania. Just as often, they were targeted attacks on sources of Muslim power and influence.

Enver Hoxha’s rise to power in the wake of the Second World War represented the culmination of this process. Dozens of muftis, sheikhs and qadis across Albania’s major cities were summarily executed. Sufi orders were disbanded, their leaders shot, and lodges and shrines demolished. Muslim institutions of learning were shuttered, and hundreds of mosques were razed. Businesses and landed estates were nationalised, stripping Muslim elites of the material bases of their wealth and influence. Islamic charitable endowments were also disbanded, bankrupting whatever Muslim social institutions remained. In several waves of repression, prominent Muslims in all fields of life were executed, and their families were interned in concentration camps.

It is worth noting that Albania’s communist regime persecuted all religions viciously and unsparingly. Enver Hoxha himself harboured a particular hatred for Catholicism. Albania’s Catholic hierarchy was publicly framed as domestic terrorists and fascist insurgents, and many were tortured and executed along with their Muslim counterparts.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries were fatal to Albania’s Muslim elite. The high culture they had built and the social, cultural, economic, and human capital they had accumulated over five hundred years were annihilated in just fifty. The traditions built up over centuries, of statecraft and governance, of war-making and diplomacy, of courtly ritual and manners in the home, of how to understand oneself and how to understand others, and how to portray those understandings in art and culture, were destroyed. The knowledge of how to rule and the sophisticated modes of embellishing and transforming their culture were disrupted as elites were exiled and killed. The socialisation of this knowledge was interrupted as institutions where elites gathered were dissolved. As wealth and property were confiscated, the material basis for sustaining what institutions and political, social, and cultural practices remained disappeared. The bottom had fallen out, and the world of Albania’s Muslim elite came to an end, and with it, the high culture they had built to express that world as beautiful and desirable.

The End of European Islam

The end of an elite does not mean the end of fancy dress balls and elaborate court rituals. It means the end of that elite’s worldview as dominant and desirable, and of its ability to spread horizontally to other elites and vertically to the rest of the population. The rise of a new elite, then, means the rise of a new worldview as dominant and desirable. In the case of Albania, the destruction of its Muslim elite meant more than the end of the construction of sumptuous palaces and the painting of charming frescoes. It meant that whatever was to come after would, without concerted efforts to rebuild a self-aware elite, be cut off from its indigenous roots and history, and stripped of its prestige and self-confidence.

Consequently, the road to re-establishing a flourishing Islam in Albania has not been easy. As the shackles of communism were thrown off, there was no elite-in-waiting with continuity to Albania’s illustrious Islamic past ready to burst onto the scene and pick up where their fathers and grandfathers had left off. Other than a few remaining pre-Hoxha leaders, like Hafiz Sabri Koçi, Muslims had to re-establish Islamic practice, propagate knowledge of the religion, and establish institutions without the considerable material and discursive support of an elite class. Influential interlocutors of Islam are more likely to be populist preachers rather than eminences grises in the halls of the prime minister’s palace. In this vacuum, both the Turkish Diyanet and the Turkish Gülen Movement have competed to build Muslim educational infrastructure, compounding the view that Islam is an import from the East.

The unravelling of Albania’s Muslim elite was not an isolated incident. Instead, the fate of Albania’s Muslim elites was archetypal of the fate of Europe’s other Muslim elites. Almost all European Muslims fell under communist rule during the 20th century. The result was consistent - violent purges of Muslim elites accompanied by the intentional destruction of Islamic high culture, the dissolution of their sensemaking institutions and the seizure of their physical wealth and capital, fundamentally disrupting the ability of Islam to propagate itself at a basic doctrinal level, let alone develop a sophisticated culture and confident sense of self within its adherents. Within the span of a few decades, the world of European Islam had come to an abrupt end, as the Balkans, Crimea, the Volga and the Caucasus all fell under authoritarian communist control.

The end of communism throughout Europe has allowed for greater religious freedom and a religious “revival” similar to that in Albania. Compared to 40 years ago, a great many more people proudly identify with their faith, whether Muslim, Christian, or otherwise, and strive to practice it openly. However, such positive developments do not necessarily create the conditions in the longue durée whereby people wish to identify with Islam and the fruits of its civilisation. Nor do such revivals necessarily spontaneously generate stable and worthwhile institutions by which an attractive and developed Islamic worldview and civilisation can pass itself on to the next generation and evolve to meet the challenges of the time. Without a conscious Muslim elite producing a worthy high culture, Islam will remain an unfashionable choice to the wealthy and powerful.

The faith of Europe’s Muslims was tempered in the crucible of the nationalist wars and communist oppression of the 19th and 20th centuries. The tenacity with which the faithful clung to the truth during the darkest periods of modern history was not contingent on maintaining prestige in the eyes of the wealthy and the powerful. However, constructing a civilisation that can protect and nurture the best within those faithful for the benefit of humanity is very much contingent on maintaining such prestige.

In Albania, as in many other European societies, the prestige of Islamic civilisation is largely forgotten because the elites who cultivated it through arts and letters, industrial endeavours, and embodied practices of statecraft and governance were annihilated. The fall of Islamic civilisation in Europe was not some vague inevitability, but is best understood as the concrete historical process of the destruction of the old Muslim elite and its attendant high culture and replacing it with a new elite and high culture.

Today, the call to prayer echoes through Tirana’s streets from the Namazgah Mosque. Albanians and other indigenous Muslims across Europe are recovering the recent history of their forefathers and the historical processes of institutional change and elite turnover which have seen their fortunes rise and fall. Perhaps, in this process of rediscovery, they may be inspired to cultivate a new high culture in the heart of Europe. 100 years from now, the Namazgah Mosque may well be at the heart of it.

Haris Khaleel is an attorney, amateur art collector and dilettante based in Canada. He is interested in early modern history and the cultural origins of institutional transformation.

You can follow Kasurian on Substack Notes, Instagram, and Twitter/X for the latest updates.

All art has been custom-drawn for Kasurian by Ahmet Faruk Yilmaz. You can find him on Instagram and X.

Well written and thought-out piece. An incredible and tragic fall for Albania from its imperial apogee to its current narco-state status and mafiotic bands operating in Switzerland and Austria

Beautifully written and informative piece, thank you.